Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art

-

December 1 2020 - July 25 2021

Curator: Dr. Adina Kamien

Associate curator: Efrat AharonDesigner: Oz Biri

-

In 1874 a diverse group of painters led by Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley presented the first exhibition of their works in Paris. Shocked by the rough, unfinished appearance of their canvases, one critic scoffed, “but this is mere Impressionism.” The word that had been used derisively was later adopted by the artists themselves and ultimately became one of the best known and most beloved terms in the history of art.

The Impressionists were reacting to the traditional values of the Academic painters, who usually chose historical or religious subjects and created smooth, technically unblemished paintings. They sought instead to capture fleeting moments in nature, painting out of doors and usually without preliminary studies.

Embarking on an intensive study of color and light, they observed that the color of an object is modified by the quality of the light in which it is seen, as well as by the colors and reflections of surrounding objects. The Impressionists’ varied brushstrokes – in lively complementary colors applied side-by-side with as little mixing as possible – coalesce into recognizable objects in the viewing process.

Reflection and the play of light on water are central elements in Impressionist paintings. Series of works focusing on the same motif transmit sensations of reality, altered by such factors as time of day, season, andweather. The artists depicted rurall and city scapes, domestic interiors, and scenes of modern daily life, responding to the rapid process of industrialization and urbanization in late-19th-century France.

The Impressionists’ colors and brush work, compositional innovations, and choice of subject matter transformed artistic theory and practice and paved the way for a revolution in painting at the turn of the century.

Paul Cézanne, French, 1839–1906, Country House by a River, ca. 1890, Oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm, Gift of Yad Hanadiv, Jerusalem, from the collection of Miriam Alexandrine de Rothschild, daughter of the first Baron Edmond de Rothschild, B66.1043

French painting of the 19th century

was characterized by variety, innovation, and prolific activity. Revolutions in industry and politics led to the rapid growth of Paris and of a class known as the Haute Bourgeoisie. The cold neoclassical style and regimented subject matter of the Academy, associated with the aristocracy, would be challenged again and again.

First came the rebellious individualism of Romantic artists, who traveled to North Africa and the Middle East in search of new themes and landscapes. Then Realist painters led by Courbet also liberated art from the confines of the studio, choosing to depict French rural settings and the daily life of country folk. Corot and the artists of the Barbizon School worked out of doors to create smaller landscapes of a darker, more melancholy, kind. Symbolists like Moreau remained in their Paris studios, painting personal visions that combined Classical mythology and Gothic aesthetics with a religious sensibility verging on the surreal.

Pierre Bonnard, French, 1867–1947, The Dining Room, 1923, Oil on canvas, 77 x 75.5 cm, The Sam Spiegel Collection, bequeathed to American Friends of the Israel Museum, B97.0487

Post-Impressionism

embraces a variety of painters, working around the years 1886–1905, who were influenced by Impressionism but took their art in other directions. The leading Post-Impressionists were four great innovators of modern art: Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Georges Seurat.

Seurat’s legacy can be studied here through the work of his associates, Paul Signac and Théo van Rysselberghe. Their Neo-Impressionist, or Pointillist, style involves the application of small units of paint according to scientific theories of color and optics. Up close, the canvas is a mass of contrasting dots, but at a distance, a shimmering, luminous image emerges.

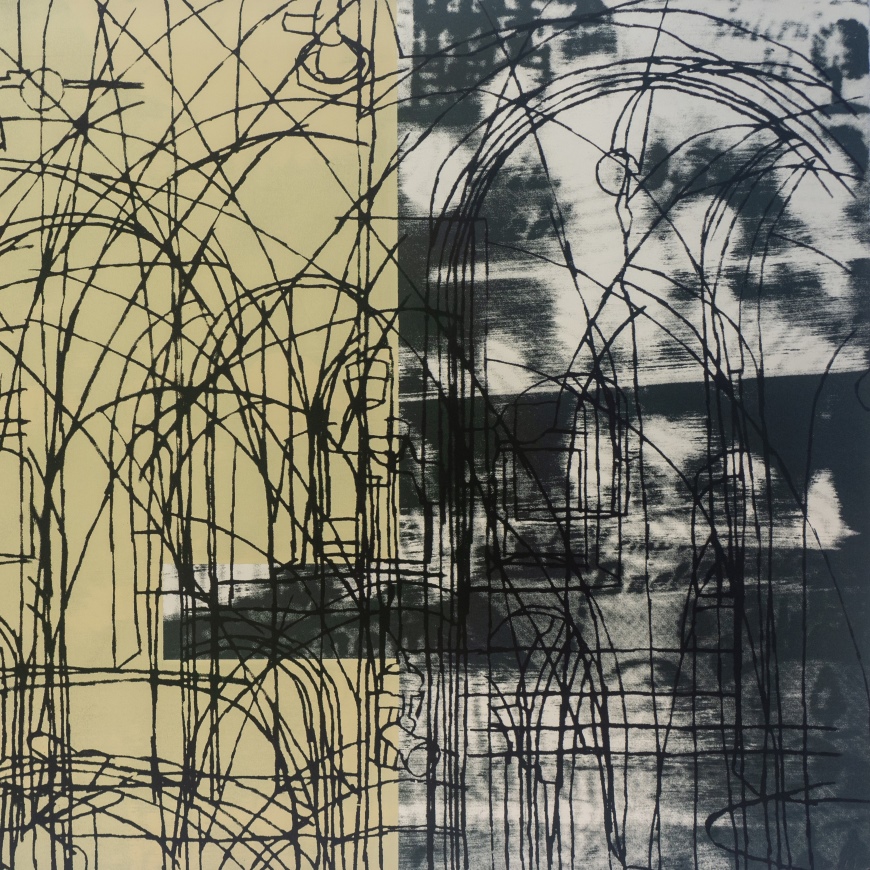

Cézanne introduced a new way of presenting depth and volume. His work reflects an understanding that the power of a picture depends on the relation of its parts to the whole. Using multiple planes or facets of color to create a sense of volume, he reduced nature, figures, and architecture to geometric forms and thus laid the foundation for Cubism. Gauguin, searching for a primordial environment untouched by modern civilization, left France for the South Seas. There he liberated form and color from the confines of Western objectivity, infusing his art with a mysterious, spiritual quality. The work of van Gogh captures the colors, tempo, and complexity of life on a viscerally pulsing surface. His frenzied brushstrokes and frequent distortion of forms expressed the artist’s own emotional turmoil.

- May 01

- May 01

- Apr 26May 02May 03May 09May 10May 16May 17May 23May 24May 30May 31

- May 03May 10May 17May 24May 31

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Apr 21Apr 28May 05May 12May 19May 26

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Apr 22May 06

- May 06May 27

- May 06

- May 06

- May 06Jun 10

- May 08May 15May 22May 29

- May 08May 15May 22May 29

- May 08May 15May 15May 22May 29

- May 08

- Apr 24May 08May 15May 22May 29