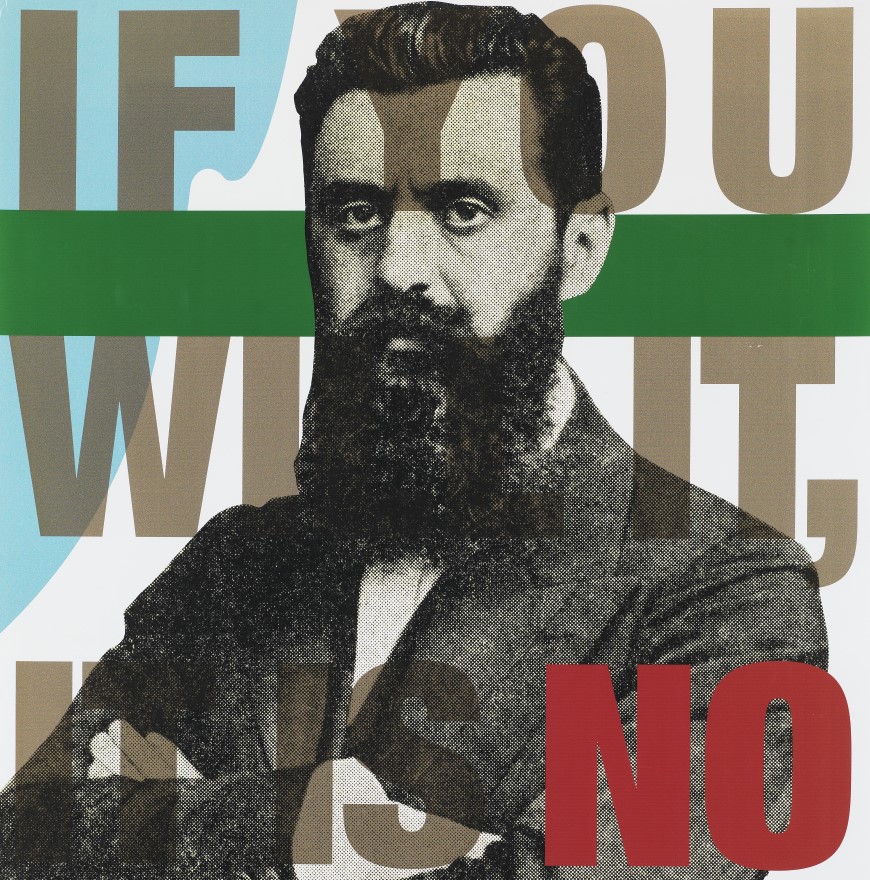

Behold the Man

Jesus in Israeli Art

-

December 22 2016 - April 16 2017

Curator: Amitai Mendelsohn

-

Maurycy Gottlieb, Marc Chagall, E. M. Lilien, Reuven Rubin, Igael Tumarkin, Moshe Gershuni, Motti Mizrachi, Menashe Kadishman, Michal Na’aman, Adi Nes, Sigalit Landau and more.

Behold the Man: Jesus in Israeli Art

What does Jesus have to do with Israeli art? Chagall encircled the tormented man’s head in a halo but also crowned it with tefillin, worn by praying Jews, and thereby transformed the crucified Christ into a symbol of Jewish suffering. The final work in this exhibition is Standing on a Watermelon in the Dead Sea by contemporary Israeli artist Sigalit Landau, in which Landau extends her hands to her sides, crucifix-like, and assumes the iconographic pose of the Virgin Mary standing atop the moon.

In between these two revealing artworks, Behold the Man: Jesus in Israeli Art unfolds the ways in which a figure that was once reviled by Jews became a source of inspiration for Jewish creativity in the 19th century and for Israeli artists during the 20th and 21st centuries. Jesus may appear overtly in their work, but often he is evoked indirectly or is present on a deeper, less conscious level. Though references to Jesus sometimes served as a bridge between two divergent religions, in most cases, Israeli artists used his figure to address a range of other issues.

View of the gallery

For centuries, the Church condemned Judaism for its failure to acknowledge Jesus as Savior of the world and held the Jews responsible for his crucifixion. The Jews, for their part, saw Jesus as the father of the anti-Semitic Christianity in whose name they were persecuted and killed; his name and image remained a despised taboo. In the 19th century, however, a number of influential Jewish thinkers, writers, and eventually artists began to draw attention to the Jewish origins of the historical Jesus. This approach aimed at reconciliation and at enhancing the position of Judaism in the Christian world – but at the same time it underscored the injustice of anti-Semitism. Reclaiming Jesus as a Jew also meant holding him up as model of the suffering his fellow-Jews had endured for generations.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Zionist artists related to the figure of Jesus in a different way, seeing the story of his resurrection as a symbolic parallel to the idea of Jewish national rebirth. After the establishment of the state, Israeli artists tended to identify with the personal anguish of Jesus the man and with his universal ethical message. They saw him as a rebel against the establishment, crucified for his opinions – an archetype of the despised artist. The image of Jesus as champion of the oppressed came to the fore in artworks that engaged with social and/or political issues such as discrimination, the human cost of war, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And it may be that the presence of Jesus – born a Jew, worshiped by Christians as the incarnation of God – in the work of Israeli artists holds out a promise of reconciliation between opposing principles: physicality and spirituality, strength and vulnerability, joined together in a figure who is both Other and brother.

The Figure of Jesus in Jewish Art

View of the gallery

Maurycy Gottlieb, Christ Teaching in Capernaum

“How deeply I wish to eradicate all the prejudices against my people . . . and to bring peace between the Poles and the Jews, for the history of both people is a chronicle of grief and anguish!” (Maurycy Gottlieb, 1879)

Maurycy Gottlieb (born Galicia, 1856–1879) may well have been the most important Jewish painter of the nineteenth century. During his short lifetime, he created a body of work that joined Polish Christian culture to his own Jewish identity in a search for reconciliation.

Christ Teaching in Capernaum shows Jesus standing in the pulpit of a synagogue built in Greco-Roman style. His body is wrapped in a prayer shawl, but his head is surrounded by the halo from Christian artistic tradition. Not all of the men and women listening to him appear to be Jewish; a man in light-colored Roman garb is particularly noticeable. The young Jew in the foreground, lost in thought with his hands on his knees, is a self-portrait of the artist.

Gottlieb’s approach clearly derives from the Jewish enlightenment view that Jesus was a great ethical teacher who never intended to abandon his own religion. The message preached by his Jesus seeks to overcome antagonism between Judaism and Christianity and hence between Jews and Poles in the artist’s own society. Gottlieb does not advocate embracing the Christian Savior, but rather returning to the authentic roots of religion, to its universal teaching of truth and love.

Maurycy Gottlieb, Christ before His Judges, 1877–79

Oil on canvas

Samuel Hirszenberg, The Wandering Jew

This monumental painting by Samuel Hirszenberg, (born Poland, 1865–1908) whose artistic career coincided with a period of violent anti-Semitic persecution in Eastern Europe, became a symbol of Jewish suffering in the shadow of the cross. A powerful image for those who believed that Jews’ misery would only come to an end with the creation of a national home in the Land of Israel, it was prominently displayed for many years in Jerusalem’s Bezalel Museum.

The painting’s subject is the Wandering Jew, the figure of Christian legend who taunted Jesus on his way to Calvary and as a result was condemned to wander the earth until the end of time. However, in contrast to the dark robes worn by the Jew in traditional depictions, only a loincloth covers the naked man portrayed by Hirszenberg, recalling Jesus on the cross. The image of the cursed Jew has been joined to that of his arch-enemy in a nightmarish scenario which suggests that the Jews will only find rest after they have escaped the shadow of the cross.

Samuel Hirszenberg, The Wandering Jew (or The Eternal Jew), 1899

Oil on canvas

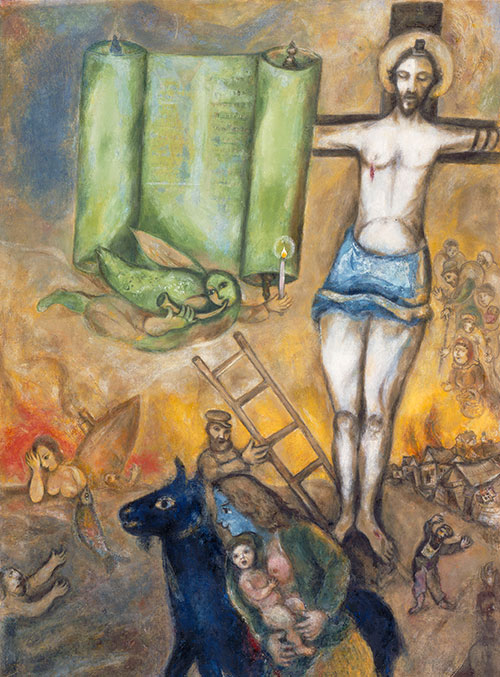

Marc Chagall, The Crucifixion in Yellow (Yellow Crucifixion)

“The people of Christ has been the Christ of peoples” (Israel Zangwill, 1892)

It was the great Russian-born Jewish artist Marc Chagall (1887–1985) who played the most important role in converting the crucifixion into an emblem of Jewish suffering. His tormented Jesus, very visibly a Jew, cries out against the anti-Semitic persecution of his brothers. During a traditional upbringing in Vitebsk, Chagall was influenced by the churches and Christian art he saw all around him, and his works contain dozens of images of Jesus, infused with autobiographical, Jewish, and universal meaning. Pope Francis I called one of them, White Crucifixion, his favorite painting.

The Crucifixion in Yellow was painted in 1943, after the German invasion of the USSR. Jesus – wearing tefillin (phylacteries), his head encircled by a halo – symbolizes the fate of the Jews. The sinking ship is the Struma, which a Soviet submarine had recently torpedoed in the Black Sea, killing nearly 800 Jewish refugees. A large Torah scroll is spread open as an extension of Jesus’ right arm, underscoring his identity as a Jew and teacher of Torah. Scenes of catastrophe appear below the cross: fleeing Jews and a shtetl going up in flames. At left, the angel and the ram’s horn usually herald redemption, but no salvation is in sight. An old Jew holds a ladder just below, a motif recalling the Deposition of Christ. Underneath are some sort of animal (a donkey? a goat?) and a woman carrying her baby. They resemble the Holy Family during the Flight into Egypt, a subject Chagall depicted many times.

Marc Chagall, The Crucifixion in Yellow (Yellow Crucifixion), 1943

Oil on canvas

Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne

Mark Antokolsky, Christ before the People’s Court

“I want to show him as a reformer who rebelled against the injustice perpetrated by the Pharisees and the Sadducees. He lived and died as a Jew for the truth and for brotherhood. This is why I choose to create him as a pure Jewish type and to depict him with a covered head.” (Mark Antokolsky in a letter to Vladimir Stasov, 1873)

Born in Vilna, Mark Antokolsky (1843–1902) was one of the most eminent Russian sculptors of the nineteenth century and also the first Russian Jewish artist to achieve renown in Western Europe. In spite of this acceptance, he suffered from the tension between his identity as a Jew and his desire to make his way as a Russian artist – especially in the field of sculpture, which until then had been closed to Jews.

In his landmark work Christ before the People’s Court, Jesus is portrayed with skullcap, sidelocks, and a robe that suggests a prayer shawl. This first sculpture to depict Christ as a Jew told his followers that anti-Semitic persecution ran counter to the teachings of Jesus, himself a Jew. By giving the figure a face that closely resembled his own, Antokolsky expressed his identification with this Jewish-born ethical role model.

Mark Antokolsky, Christ before the People’s Court, 1876

Marble | Haifa Museum of Art

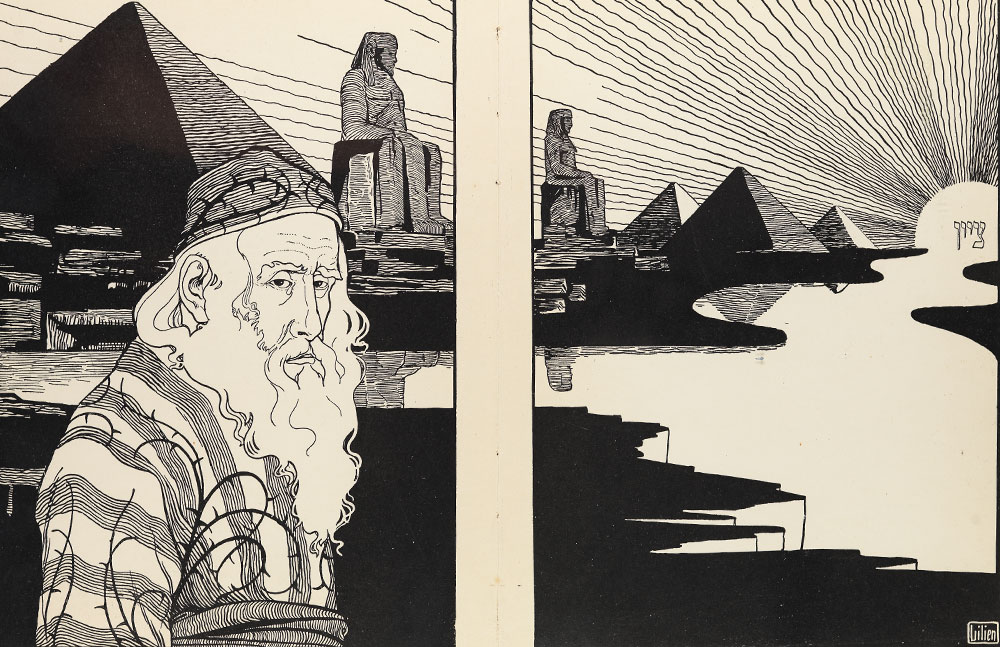

Between Judaism, Zionism and Christianity: Ephraim Moses Lilien

It was Ephraim Moses Lilien (1874–1925), born into traditional Jewish society and emerging as an artist in the cultural centers of Central Europe, who molded the visual representation of Zionism in its early years. A unique fusion of Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) eroticism and fantasy with early Zionist pathos and idealism, Lilien’s art managed to combine Jewish and Christian symbols, Orientalism, and influences from ancient Egypt and Assyria. This eclectic East-West style, which has been dubbed Judenstil, became his personal hallmark.

Lilien’s national Jewish art subtly resonates with the Christian idea that the return of the Jews to Zion was a precondition for the Second Coming, which led many Christians to align Zionism with redemption. Without depicting Jesus, his illustrations include crowns of thorns, crucifixions, and iconography associated with Mary. These motifs are imbued with Zionist meaning, whether serving as signs for Jewish suffering in the Diaspora or proclaiming a proud determination to achieve national resurrection in the Land of Israel.

Pesah

Lilien’s illustrations to a book of poems by the German writer Börries von Münchhausen transformed him into the preeminent Zionist artist almost overnight. This joint venture, which appeared in 1900 under the title Juda, was based on stories from the Hebrew Bible and presented a stirring view of ancient Israelite history. The illustrations set out for the first time Lilien’s distinctive Jewish-Zionist visual language combining Jugendstil motifs, Jewish biblical images, implicit Zionist messages, and Christian iconography.

In Pesah (Passover), an old Jew stands in the foreground, pyramids behind him and to the right a rising sun with the Hebrew word Zion at its center. Thorny tendrils wind around the Jew’s skull-cap and his body. In Christianity, the crown of thorns with which Roman soldiers mockingly placed on Jesus’ head is perhaps the most familiar Instrument of the Passion. Here, the motif alludes to the pain and subjugation of Israel, suggesting that just as the Israelites were freed from Egyptian bondage in the Passover story, the Jews of the Diaspora will be redeemed by Zionism. Although this symbolism daringly likened the old Jew to Jesus, the imagery was subtle enough to escape the notice of a traditional Jewish public.

Ephraim Moses Lilien, Passover, Illustration to Juda by Börries von Münchhausen, Berlin, 1900

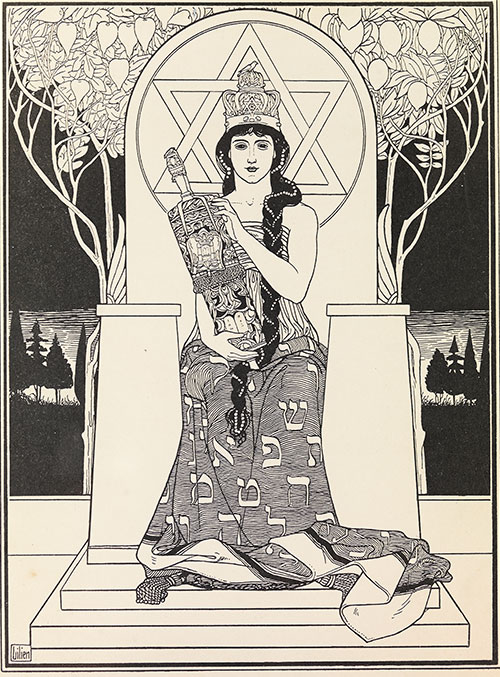

The Sabbath Queen

Proudly cradling a Torah scroll in her arms, a young woman wearing a crown and a garment embroidered with Hebrew letters sits on a massive throne. The headrest with its enormous Star of David frames her head like a halo. The visual similarities resonate strongly – can it be that Lilien based his Sabbath Queen on iconography of the Maestà, the enthroned Madonna holding the baby Jesus? And in doing so, transformed a Christian image of exultant majesty into a Jewish emblem of restored pride and glory?

Ephraim Moses Lilien, The Sabbath Queen, Illustration to Juda by Börries von Münchhausen, Berlin, 1900

The National Library of Israel, Jerusalem

Dedicated to the Martyrs of Kishinev

In response to the 1903 attack on the Jews of Kishinev, Lilien created an image that played a central role in the campaign to protest the outrage and raise funds for the survivors. An old Jew wrapped in a prayer shawl has been tied to a stake, flames licking at his feet. An angel appears behind him holding a Torah scroll, lifting up the martyr’s soul with a kiss. The form of the angel’s huge wings suggests a cross, while the sun or moon in the background acts as a halo over the old man’s head. Rembrandt’s famous etching of the Binding of Isaac, in which the angel hovers over the shoulder of an aged Abraham and embraces him, evidently had a strong influence on this work. But in Lilien’s portrayal, Abraham becomes the martyr of Kishinev, sacrificed because he is a Jew.

Ephraim Moses Lilien, born Galicia, Dedicated to the Martyrs of Kishinev

from the periodical Ost und West, Berlin, 1904

The National Library of Israel, Jerusalem

Man of Sorrows and Zionist Messiah: Reuven Rubin

“The nails in Jesus’ hands and feet are those that burn me, and no one can comprehend my suffering.” (Reuven Rubin, 1922)

The work of Reuven Rubin became synonymous with what is known as Land-of-Israel Zionist art, but Christian themes played a role in the paintings Reuven Rubin created in Europe and also after his arrival in Palestine in 1923. On a personal level, he identified with Jesus, regarding him as a misunderstood, persecuted spiritual figure. In a national context, he saw Jesus as a symbol of the exile the Jews needed to leave behind in order to achieve self-fulfillment and regeneration – and also, unusually, as an image of Zionist rebirth. Marc Chagall likewise regarded Jesus as an alter ego and as a symbol of Jewish suffering, but Reuven was the first to connect the figure of Jesus to that of the New Jew and the pioneers living in their homeland after two thousand years of exile.

View of the gallery

Temptation in the Desert

"That figure in the middle is myself . . . resisting temptation, continuing on my way of suffering in spite of the hands that reach out to grasp me. . . . she [the woman] is trying to hold me back, but I am (going on. I shall go on!)” (Reuven Rubin, 1918)

This key early painting by Rubin (born Romania, 1893–1974) brings to mind two New Testament stories that had become popular subjects in Christian art: Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane immediately before his arrest (the Agony in the Garden) and his encounter with Mary Magdalene after rising from the tomb, when he warns her not to touch him (Noli me tangere). In Rubin’s portrayal of the confrontation with worldly temptation – the title also refers to a third episode in the life of Jesus, the Temptation in the Desert – a poignant image of personal supplication is joined to defiance of a woman who evokes the seductive femme fatale.

Although not an overt self-portrait, Rubin did tell an interviewer that he modeled the face of the central figure after his brother, who died during World War I, but also saw himself in the tortured ascetic. Thus the painting can be considered a rare early example of a Jewish artist daring to identify with Jesus.

Giovanni Bellini, The Agony in the Garden, ca. 1465, The National Gallery, London

Reuven Rubin, Temptation in the Desert, 1921

Oil on canvas

Tel Aviv Museum of Art, gift of Kaye Lee Wrage Gunn, Dallas, to the American Friends of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art

The Encounter

The Encounter is one of the most intriguing and enigmatic of Rubin’s early works. A weary elderly Jew sits, head bowed, at one end of the bench. At the other end sits Jesus with his stigmata; he has been crucified, but now he is resurrected and sits upright. This encounter suggests the legend of the weary Wandering Jew, punished with eternal homelessness for his taunting of Christ.

A tree with drooping branches stands beside the old, bent Jew, while a burgeoning tree grows upward next to Jesus. The visual juxtaposition of defeated Judaism and triumphant Christianity echoes the longstanding motif of Ecclesia (the Church) overcoming Synagoga – but here the meaning is quite different. Early-20th-century Zionist imagery contrasted the withered past with the fertile growth of a new era; in this painting, Rubin may also be suggesting a more daring symbolic analogy between the Zionist movement’s mission to bring the Jewish people back to life and Jesus risen from the dead.

Reuven Rubin, The Encounter (Jesus and the Jew), 1922

Oil on canvas

Collection of the Phoenix Insurance Company Ltd., Tel Aviv

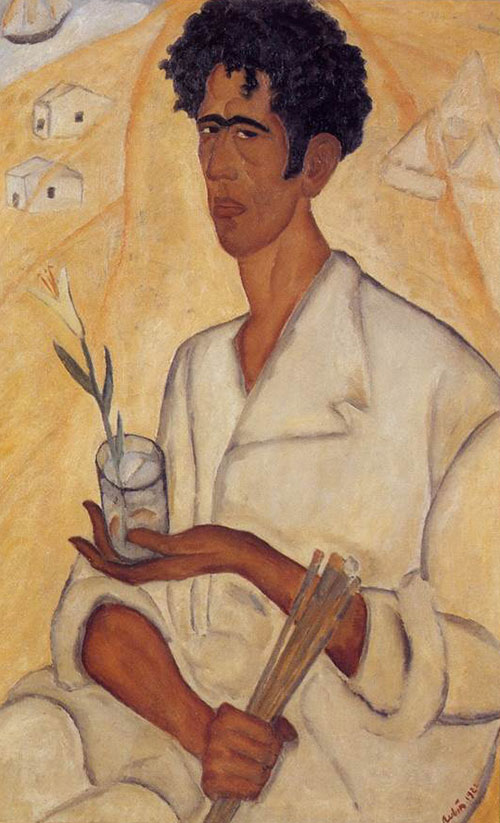

Self-Portrait with Flower

Shortly after arriving in the Land of Israel, Rubin paints himself in the white shirt of a pioneer, seated against a characteristic background: sand dunes, three tents, two houses, and a corner of the sea with a boat. His right hand clutches a fistful of paintbrushes, while his left holds a glass containing a white lily. Also known as a Madonna Lily, this flower is familiar from depictions of the Annunciation: it is the attribute, the distinguishing symbol, of Mary. Just as saints were portrayed in Christian art holding their attributes, Rubin’s paintbrushes identify him as an artist. The lily also suggests that he sees himself as the bearer of glad tidings, perhaps even as a messiah of Zionist painting in the land. His mission: to herald – and to create – a newborn art that will accompany the momentous change occurring in the life of the Jewish people.

Reuven Rubin, Self-Portrait with Flower, 1923

Oil on canvas

Rubin Museum, Tel Aviv

The Madonna of the Vagabonds

The Madonna of the Vagabonds, painted in Bucharest the year before Rubin left for Palestine, suggests an analogy between the infant Jesus and the pioneer reborn in the Land of Israel. With its brighter palette, the painting heralds Rubin’s new Land-of-Israel style and reflects the optimism he experienced on the eve of his immigration.

The hopeful light of dawn illuminates the scene. In the background is the Sea of Galilee, upon which Jesus is said to have walked and where he gathered many of his disciples, simple fisherman. Three empty boats float on the water, presumably belonging to the men asleep on the shore and about to awake to a new era of redemption. These are the “vagabonds” who arrived at this shore at the beginning of the 20th century to be pioneers in the old-new land.

The Madonna looks down at the infant, not in the adoring pose of many traditional Christian depictions that show her venerating the baby Jesus, but with her bared breast emphasizing her fecundity and a smile on her lips. The fact that she is seated solidly on the ground conveys simplicity and rootedness. In composition, the painting closely resembles the earlier Temptation in the Desert, but this mother is the antithesis of a femme fatale, and the work’s message is entirely different. Instead of sexual repulsion, asceticism and anguish, the Madonna of the Vagabonds and her baby signal fertility, the renewal of nature, and the advent of redemption.

Reuven Rubin, The Madonna of the Vagabonds, 1922

Oil on canvas

Rubin Museum, Tel Aviv

From Personal Experience to National Identity: 1930's-1960's

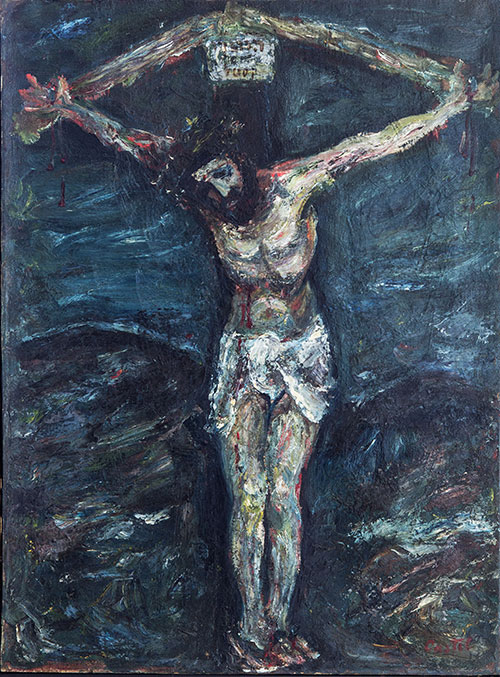

Moshe Castel, Untitled (The Crucified)

“. . . Jesus cried with a loud voice, ‘Eli, Eli, lama sabakhtani?’ that is, ‘My God, my God why hast thou forsaken me?’” (Matthew 27:46)

The story behind this dark crucifixion by Moshe Castel (1909–1991), a painter known for his depictions of Jewish religious and national subjects, must be sought in Castel’s personal history. The work was created when the artist secluded himself in a monastery near the Sea of Galilee in order to recover from the loss of his first wife, who died in childbirth, and the death of their daughter three years later. Discovered in a locked cupboard in Castel’s house in 1992, the painting – which is highly unusual in the context of his work and that of his Israeli contemporaries – is now displayed to the public for the first time.

In an expressive style influenced by Chaim Soutine, and inspired by Marc Chagall’s crucifixions, Castel put himself on the cross. The face is a self-portrait, while above the figure a Hebrew inscription says “Castel the Jew,” so that the artist’s intense outpouring of pain culminates in total identification with the suffering of the crucified Christ.

In two sketches from the same period, the Hebrew inscriptions above the figure read “Jesus” and “Jesus of Nazareth.” They give the full name Yeshu’a rather than the more common Yeshu, which was often read derisively by Jews as an acronym for “may his name be obliterated,” and may indicate the painter’s rejection of this traditional revulsion and his own positive perception of Jesus.

Moshe Castel, Untitled (The Crucified), 1940s

Oil on canvas

Moshe Castel Museum of Art, Ma’ale Adumim

Leopold Krakauer, Jesus/Tree

The “Jesus/Tree” series by Leopold Krakauer (1890–1954) reveals a complex relationship between this architect-artist from Vienna and the landscape in which the story of Jesus is set. Against dark, turbulent backgrounds, the olive tree, a symbol of the East, is fused with the figure of Jesus – who became a Western symbol, but whose roots likewise lie in the East. The first work in the series dates back to 1927, three years after Krakauer’s arrival, while the final drawings are from 1940–41.

Living in Jerusalem, Krakauer was inspired by its olive trees, including those in the Valley of the Cross, where, according to Christian tradition, the Romans cut down the tree from which they fashioned the cross. But his bleak depictions lack the hope for salvation that Christianity associates with the crucifixion: although an instrument of death, the cross symbolizes life and atonement for the Original Sin of having eaten from the Tree of Knowledge. That comfort is lacking here. Adapting to his new environment and presumably influenced by the troubled events of his time, Krakauer evokes the suffering of Jesus in portrayals of an anguished Jerusalem landscape.

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” (Matthew 5:10)

Leopold Krakauer, Jesus Tree, 1949

Chalk on paper

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Extended loan from Trude Dothan, Jerusalem

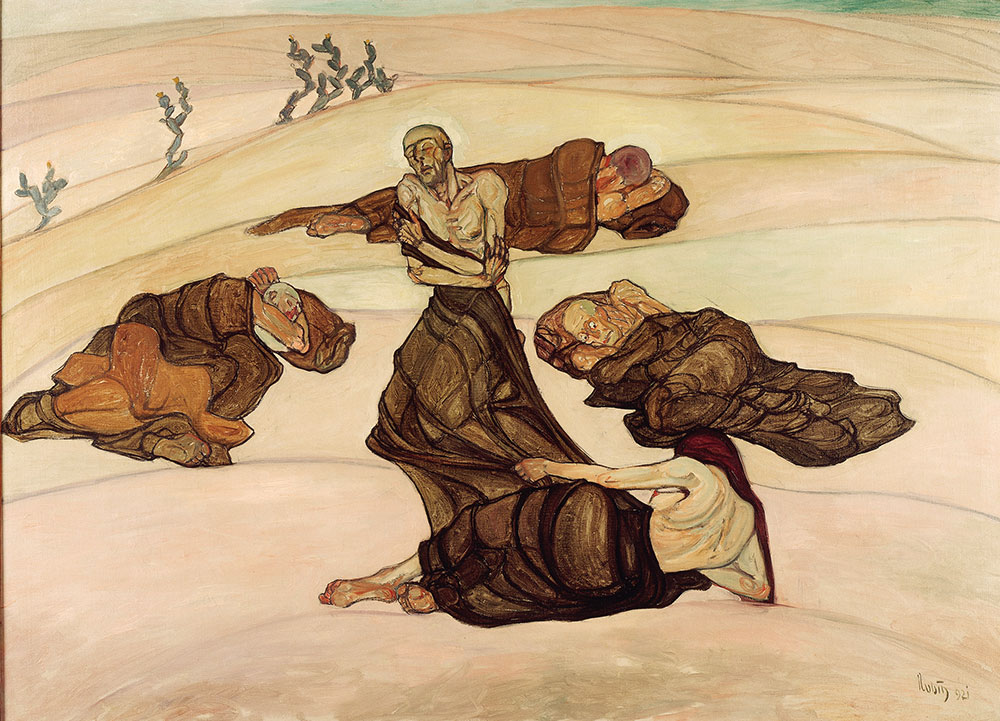

In the Courtyard of the Third Temple

Naftali Bezem (born 1924) incorporated Christian imagery in the works seen here, giving motifs associated with Jesus a unique, personal interpretation and relating them to contemporary events and social concerns. In the Courtyard of the Third Temple is a horrified response to the 1956 Kafr Kassem massacre, when border policemen opened fire on villagers who were on their way home from working in the fields, unaware that the Sinai War had broken out and a curfew had been imposed on Arab settlements in Israel. Almost fifty people, including women and children, were killed.

Bezem’s painting is clearly influenced by Pablo Picasso’s 1937 anti-war masterpiece, Guernica. Three women in anguished poses are portrayed alongside a dead man whose hand still clutches an Israeli identity card – a further indictment of the state and its treatment of Arab citizens. The work’s ironic title denounces the fact that such a thing could occur at a time when Israel has just been reborn as a nation, in what might be called the period of the Third Temple. The three women suggest Mary mother of Jesus, Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene, key figures in depictions of the lamentation over Jesus’ body. In Bezem’s painting, the three women are positioned alongside the slain villager and, for the first time, the figure of Jesus is invoked by a Jewish artist to portray a Palestinian victim of the Jews and not to indict Christian anti-Semitism.

Naftali Bezem, In the Courtyard of the Third Temple, 1957

Gouache on cardboard

Tel Aviv Museum of Art; Dizengoff Prize for Painting and Sculpture 1957

Marcel Janco, Genocide

The modernist Marcel Janco (1895–1984), who participated in the transformative artistic movements of prewar Europe, also derived inspiration from traditional Christian painting – most notably from depictions of two important scenes from the story of Jesus: the Lamentation and the Entombment. These portrayals of sacrifice, death, and the hope for resurrection, at once dramatic and poignant, offered him a way to create empathic multilayered responses to human suffering.

In Genocide, painted in 1945, the position of the open-mouthed naked corpse recalls Hans Holbein’s masterwork The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, 1521. The complete nakedness of Janco’s figure (rarely found in depictions of Jesus) and the bent leg convey the horrors of a genocide in which the dead lost all dignity. Although painted in the Land of Israel, Janco’s work belongs to the tradition of Jewish and international art that linked the victims of the Holocaust to the figure of Jesus.

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, 1521, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel

Marcel Janco, Genocide, 1945

Oil on Masonite

The Janco-Dada Museum, Ein Hod

Moshe Hoffman, 6,000,001

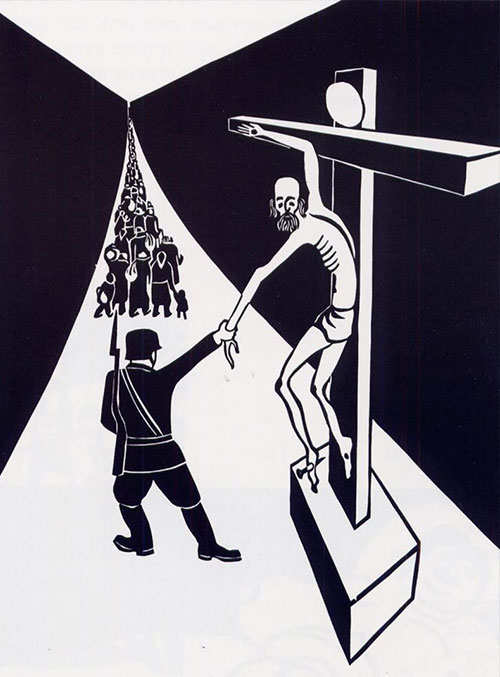

Another artist to use the figure of Jesus as a symbol of Jewish victimhood in the Holocaust is Moshe Hoffman (1938–1983), who had an Orthodox upbringing and survived the war in Budapest together with his mother and brother.36 Hoffman specialized in sculpture and woodcuts, his oeuvre including erotica and many two- and three-dimension portrayals of the female body. However, in 1967 he set aside his usual themes to create an exceptional and important work: a series of ten woodcuts devoted to the Holocaust and entitled “6,000,001” – one of the most forceful responses to the Holocaust ever produced by an Israeli artist. Almost every one of these prints either contains the figure of Jesus or makes use of Christian iconography. The title “6,000,001” hints at one additional Shoah victim: Jesus. In his autobiography Hoffman wrote: “The ‘One’ denotes the death of divinity and the demise of faith in man, Jewish and Christian alike."

Moshe Hoffman, Untitled, from the “6,000,001” series, 1967

Woodcut

Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

Violence and Compassion | Moshe Gershuni

Moshe Gershuni

“. . . for this is my blood of the new covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” (Matthew 26:28)

For many years now, the art of Moshe Gershuni (1936-2017) has been profoundly connected to Christian themes. Although Jesus is not depicted explicitly, his presence is intimated through the motif of blood and through visual signs, such as the cross, that leave no doubt about his centrality in Gershuni’s work. Another key concern is the tension between Judaism, invoked through numerous quotations from Jewish sources, and the European Christian high culture that reached a deplorable low in the sins of the Second World War.

The early 1980s saw a transformation in Gershuni’s art when the acknowledgment that he was gay coincided with an emotional breakdown. As part of an intense psychotherapeutic process, he began to paint with all of his body – using his hands and crouched on all fours – and he also explored new subjects: Judaism, the Holocaust, and homosexuality. The tension between spirit and flesh that is fundamental to Christian belief in the incarnation of God is also inherent to Gershuni’s work, in which physicality confronts the divine, and the earthly embraces that which is exalted and sublime.

With the Blood of My Heart

The three plates displayed here were part of an installation mounted by Moshe Gershuni as he prepared for his exhibition representing Israel in the 1980 Venice Biennale. In one space, an easel held a sheet of glass on which the words Mein Purpur is sein teures Blut (“My royal purple is his [Jesus’] precious blood”) from Bach’s Cantata No. 75 were painted in red. In the adjacent room, 150 white plates splashed with blood-red paint were placed on the floor. These “bloodstains” had pooled into various forms within the plates.

In Judaism, blood is equated with life itself, and its consumption is forbidden: “Only be sure that you do not eat the blood, for the blood is the life” (Deut. 12:23). In Christianity, however, the wine that is drunk during the Eucharist is believed to be Jesus’ blood, the blood sacrificed by the Lamb of God for the salvation of the faithful: “Jesus said to them, ‘. . . he who . . . drinks my blood has eternal life’” (John 6:53–54).

Gershuni’s focus on red is connected to his artistic engagement with what is debased and uncivilized and with his preferred painting position in the early 1980s – crawling on all fours, “the position of a wounded, enraged animal or a man whose soul is embattled.” With the Blood of my Heart represents a new covenant Gershuni made with his body and with the world when his art took a different direction. Abandoning his restrained, cerebral approach for an outpouring of emotion, he confronted – and forced the viewer to confront – the blood of torment, of sacrifice, and of redemption

Moshe Gershuni,Objects from the installation With the Blood of My Heart, 1980

Three plates with glass paint

Benno Kalev Collection

There / Name

This opened-out shoebox forms a cross, while the Star of David drawn against a yellow background clearly evokes the yellow star that Jews were forced to wear during the Holocaust. At the top, Gershuni wrote a single Hebrew word which can be read as both sham (there) and shem (name).

In Israeli culture, “there” denotes Europe, the Old World, and the exile of the Diaspora, often alluding more narrowly to the Shoah and the places where it unfolded. At the bottom of the work, the artist quoted from Deuteronomy 14:23: “as it is said: to place His name there” – meaning that God will dwell in that place. Gershuni’s use of these words introduces a pointed, powerful contrast between presence and absence, the absence of God in the “there” that was Europe during the Holocaust. There / Name (along with similar works created by the artist) has been called a “Jewish icon”: although shaped like the Christian cross, it bears the symbol of Jewish sacrifice.

Moshe Gershuni,There / Name, 1987

Oil, industrial varnish, pencil, and fist imprint on shoe box

Private collection

Hai Cyclamens

“Hai Cyclamens,” a group of large-scale paintings from 1983 and 1984, distilled Gershuni’s engagement with Judaism, Israeliness, homosexuality, and Christianity into a single body of work.

In Israeli culture, through seminal poems and songs, the cyclamen is associated with vulnerability and the death of young soldiers. Hai (in numerical terms equivalent to 18) means “life.” Despite the series’ title, it is a banana tree that occupies the center of each painting, with cyclamens appearing only at the edges. The upward and sideward movement of trees and leaves produces phallic shapes that also recall the form of Jesus’ crucified body. Gershuni’s combined references to growth, sexuality, and crucifixion parallel the tension between life and death. Each painting is made up of two sheets joined by a conspicuous horizontal strip of black adhesive tape, adding to the formal suggestion of a cross. Around the images are words from Psalms 103:3–4 (“Who forgives all your iniquities, heals all your diseases . . .”) that take us from sin through healing to redemption and mercy.

Moshe Gershuni, From the “Hai Cyclamens” series, 1984

Glass paint, industrial varnish, oil stick, charcoal pencil, masking tape, and other materials on coated paper

Collection of the Phoenix Insurance Company Ltd., Tel Aviv

Igael Tumarkin

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace on earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.” (Matthew 10:34)

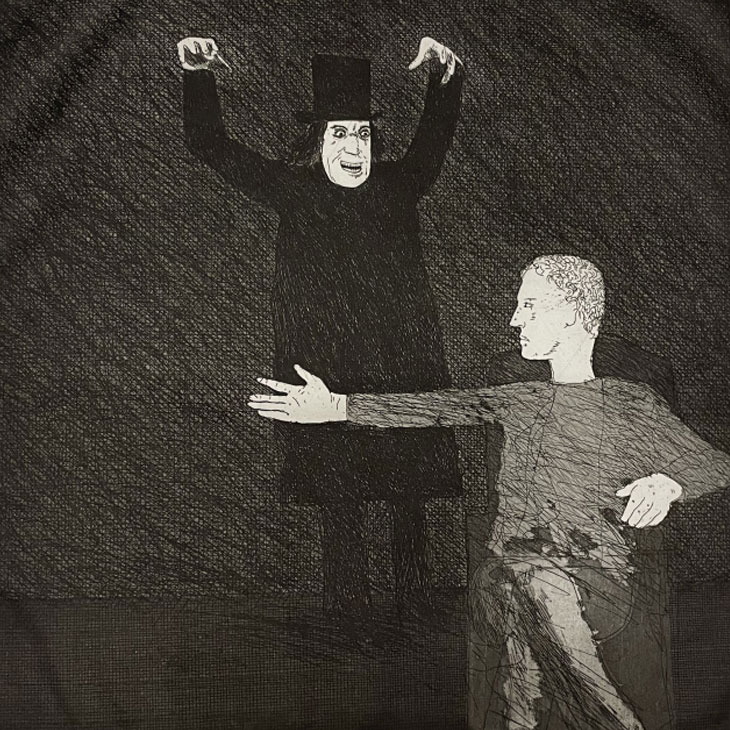

The work of Igael Tumarkin (born 1933) has always drawn on Christian imagery and masterworks by other artists as part of a perpetual dialogue with European culture. Tumarkin reveres the rich artistic heritage of the West, but at the same time he holds its culture responsible for horrific violence and destruction. The biological son of a German Christian father, raised by his Jewish mother, he has taken the crucifixion as a personal and collective symbol that he revisits time after time.

In some of his work, the sacrifice of Jesus appears together with military weapons in order to address the victims of war and discrimination, part of Tumarkin’s harsh critique of the Israeli establishment. His Christian symbolism is in itself a pointed attack on the local view that Christianity constitutes a threat to Israeli identity and cultural hegemony. Enfant terrible, wrathful prophet, and groundbreaking artist, Tumarkin sees himself as not only misunderstood, but something of a pariah. In this sense, he carries on the tradition of painters such as Gauguin and van Gogh, who identified with the spurned Otherness of Jesus. His engagement with the figure of Christ has resulted in a dense, dramatic oeuvre that condemns injustice and shows the wrongs of humanity no mercy.

Mita Meshuna

A partly open military cot produces the form of a cross, at its top the inscription MITA MESHUNA above a piece of blue-and-white cloth that resembles a tattered, drooping Israeli flag. Meshuna means “strange,” but this is a pun, since the Hebrew word pronounced as mita means both “bed” (thus “strange bed”) and “death.” The expression “strange death” originates in the Talmud and refers to an unnatural or unusually painful death.

Mita Meshuna suggests that the soldier who dies a painful and untimely death has been sacrificed by society and is therefore the victim of a crucifixion, a sort of Jesus. The work was created in response to the many casualties of the First Lebanon War, which many Israelis vociferously condemned as an unnecessary war. Tumarkin’s crucified soldier, who symbolizes weakness rather than military might, was controlled by an establishment that remained impervious to the will of the people. Tumarkin has done more than demean the flag in this work; he has joined it to Christianity’s emblem in order to make his protest against the victimization of the powerless all the more outspoken and – in an Israeli context – shocking.

Igael Tumarkin, Mita Meshuna (The Artist's Monogram), 1984

Wood, fabric, soil, paint

Bedouin Crucifixion

In Bedouin Crucifixion, Tumarkin asserted his empathy with Bedouins struggling against government-sponsored evictions and land confiscations. The hybrid cross he constructed consists of horizontal wooden branches – used by the Bedouin as tent-poles – and an industrial iron vertical backdrop against which a soft assemblage of pieces of cloth and other organic materials is “crucified.” The rigid metal structure seems to symbolize the callous Israeli establishment that victimizes the poor and the helpless, in this case a Bedouin who takes the place of Jesus.

One of Tumarkin’s most important sources of artistic influence was the renowned Isenheim altarpiece painted by Matthias Grünewald. In Bedouin Crucifixion, the spare wooden branches recall the emaciated arms of the Isenheim Christ and, along with the bowed tree-stump head, recreate something of the gaunt horror of Grünewald’s depiction.

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, 1512–16, Musée Unterlinden Colmar

Igael Tumarkin, Bedouin Crucifixion, 1982

Soil and mixed media on iron plates

Pain and Redemption

“For when I am weak, then am I strong” (2 Corinthians 12:10)

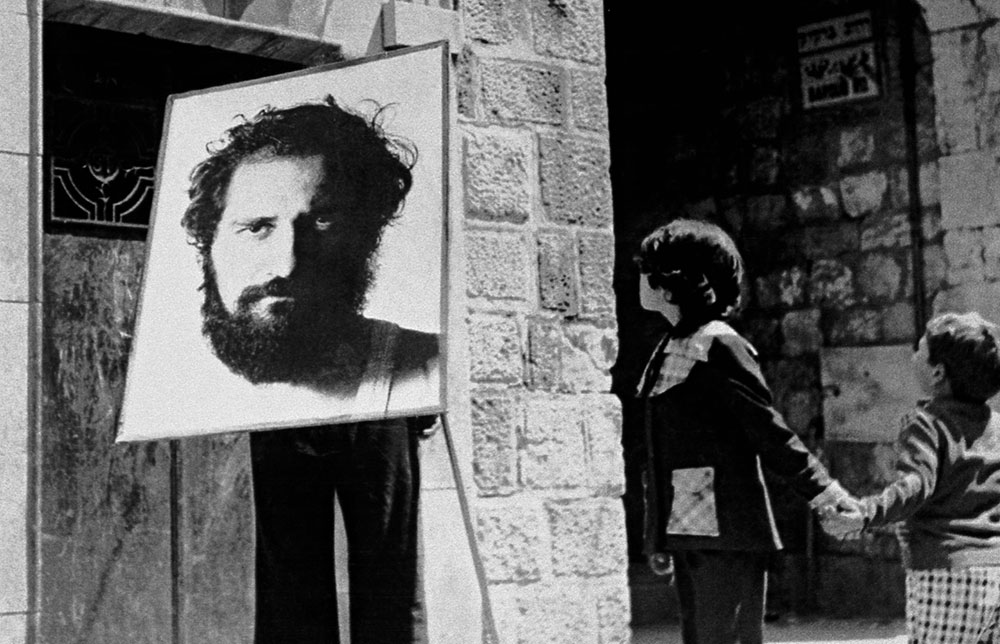

Motti Mizrachi, Via Dolorosa

In 1973 Motti Mizrachi (born 1946) walked on his crutches the length of Jerusalem’s Via Dolorosa, the route taken by Jesus on his way to the crucifixion. Jesus bore the cross as he traversed his road of suffering; the young performance artist, who had been disabled since childhood, carried an enormous photograph of his own face. This unusual act of engagement with the figure of Christ, a defining start to Mizrachi’s career, operated on a number of levels – personal, social, and artistic.

In personal terms, the artist regarded pain, “the only certainty” in life, as a step on the path to healing and a tool that could be used to arrive at something much more cosmic. He identified with Jesus’ transformation of physical frailty into spiritual might, a fundamental model in Christianity. Via Dolorosa also references the Jesus who represented the downtrodden, preaching a social message that would inspire 20th-century liberation movements. In the Israeli context, Mizrachi’s work coincided with the early organized struggle of Jews of North African origin, victims of discrimination, and was interpreted as an act of social protest. Finally, on an artistic level, Mizrachi raised questions about the power of the image: despite his identification with the qualities Jesus symbolized, he sought to critique the use and misuse of iconic portraits, whether religious or secular.

Motti Mizrachi, Via Dolorosa, 1973

Lambda print

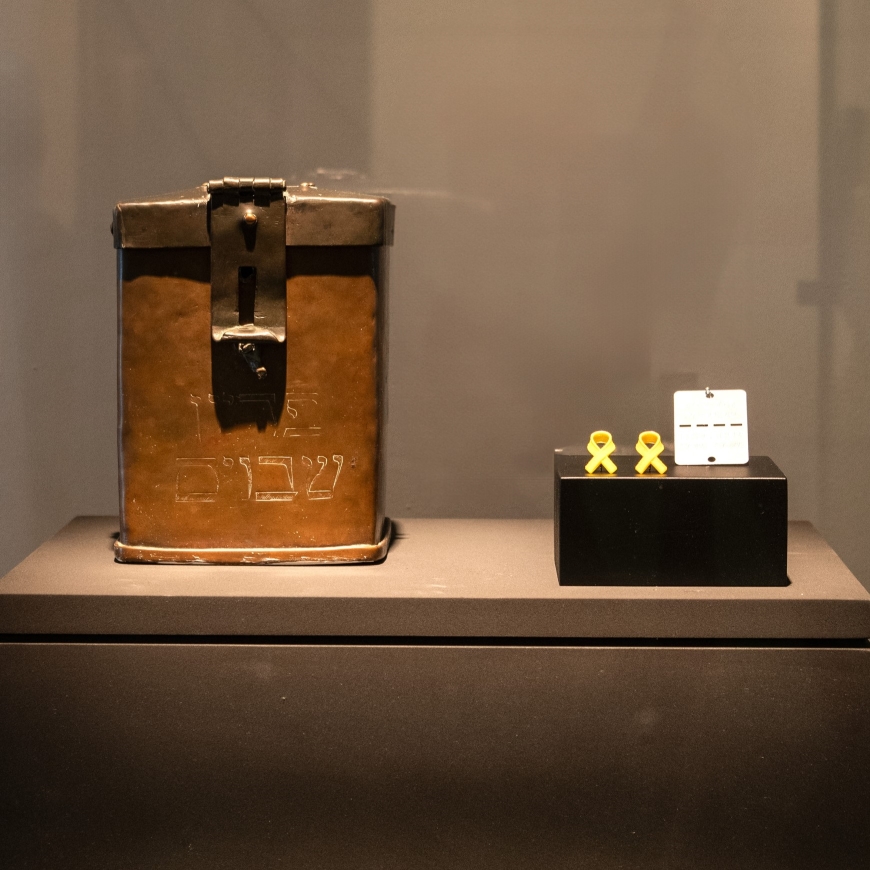

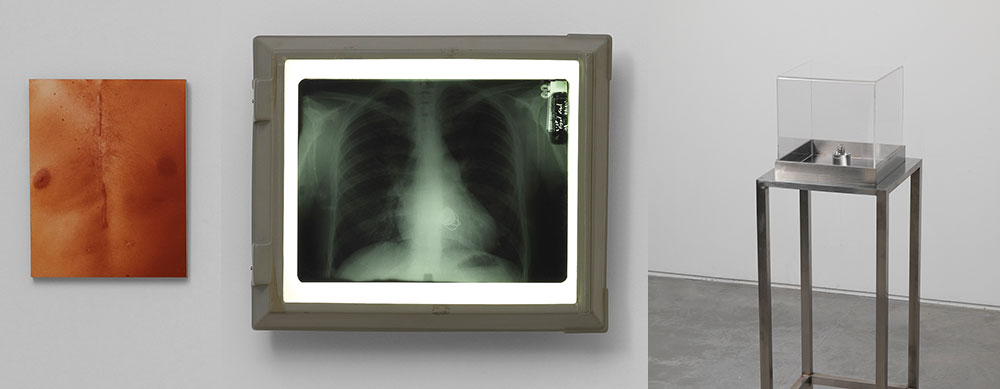

Gideon Gechtman, Exposure

“I am he that liveth, and was dead; and, behold, I am alive for evermore” (Revelation 1:18)

Disease, death, and commemoration are central to the work of Gideon Gechtman (1942–2008), who first emerged as an artist through his groundbreaking 1975 installation Exposure. As treatment for the heart condition that eventually killed him, Gechtman had undergone surgery to replace a defective valve, and the many objects in the installation related to his ordeal: test results, hair that had been shaved before the operation, a chest x-ray alongside a photograph of the incision scar, and an example of the artificial valve that had been inserted. Three of these objects are exhibited here.

The heart has very clear associations in Christianity: the pierced Sacred Heart of Jesus represents a wellspring of love, offering believers the promise of eternal life. It was a popular subject for visual portrayal, as was the wound in Christ’s side, seen as a gateway to everlasting salvation. In Gechtman’s work, the artificial valve symbolized the artist’s revival of a heart that was about to fail – and thus, temporarily, a victory over death itself. Unlike the Sacred Heart with its supernatural connotations, the mechanical heart valve testified to the advances of modern medicine, functioning successfully for 27 years and in that sense assuming God’s role as healer and giver of life.

Gideon Gechtman, Valve, 1975/1980

Stainless steel and Perspex

Collection of Bat-Sheva Gechtman and Noam Gechtman

Gideon Gechtman, Exposure, detail from installation, 1975

Gelatin silver print on plywood

X-ray photograph in lightbox

Collection of Bat-Sheva Gechtman and Noam Gechtman

David Ginton, Pain (Bed)

In the 1970s the work of David Ginton (born 1947) tested the boundaries of physical pain, often in the context of Christian iconography. Inspired by the suffering of Jesus during the Passion, pain has played a central role in Christianity, at times voluntarily assumed by the pious and horrifyingly depicted in artwork relating to martyrs. In Pain (Bed), Ginton lay face-down on the floor, with the legs of a bed pressing into his hands and feet in a manner reminiscent of crucifixion. In other works, he pressed a stone into the sole of his foot or covered his hands in bandages on which he wrote the Hebrew word for pain. There is no religious sentiment behind these ironically self-conscious works, despite their deliberate allusions to Christianity. And unlike Jesus’s pain, his suffering is not intended to save the world – it is entirely personal.

David Ginton, Pain (Bed), 1974

Gelatin silver print

The Lamb of the World

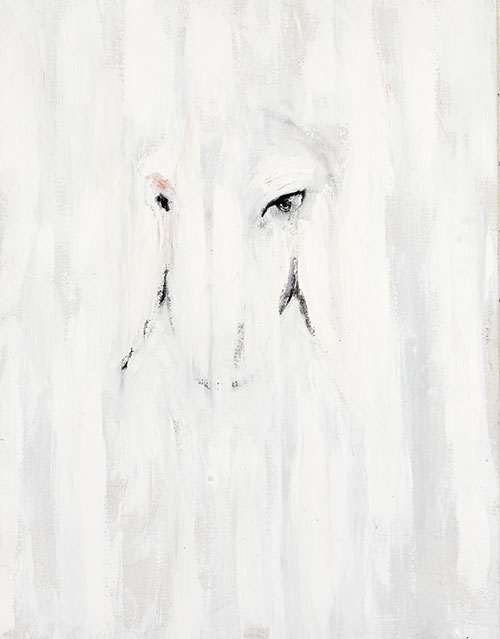

Menashe Kadishman, Untitled

“. . . like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a ewe that before her shearers is dumb, so he opened not his mouth.” (Isaiah 53:7)

The image with which Menashe Kadishman (1932–2015) is most closely associated is the sheep or lamb. In Israeli art, the sheep is a characteristic local image, almost emblematic of the landscape, but Kadishman saw this animal as an emblem of sacrifice and called it a “symbol of the death of young men in Israel’s wars.”

In Christian theology, Jesus is the Lamb of God (Agnus Dei), the sacrifice that took upon itself all the sins of humanity. Although there is no end to visual portrayals of the Lamb, these do no include depictions of its face alone, which became a hallmark of Kadishman’s work. However, depictions of Jesus’ face abound, and the miraculous portraits that are regarded as his “true image” have unique religious importance. In European tradition, the sweat on Christ’s face as he bore the cross to Calvary left his imprint on Veronica’s Veil; in the Eastern Church, the equivalent to this image is the Edessa Mandylion. In the Mandylion, Jesus’ face in isolation from his body bears a curious resemblance to Kadishman’s heads of sheep.

Two visual traditions – the portrait of Jesus and the Lamb of God – come together in Kadishman’s work, and the Christian symbolism of the sacrificial lamb hovers over his Israeli icons.

The Holy Face (The Mandylion), 14th century, Church of St. Bartholomew of the Armenians in Genoa

Menashe Kadishman, Untitled, 1999

Acrylic on canvas

Rachel and Dov Gottesman Collection, Tel Aviv

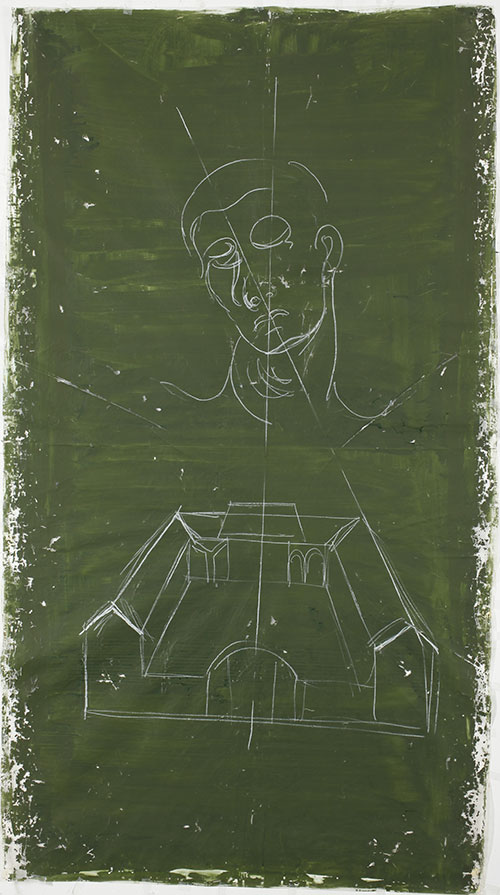

Tamar Getter, Tel Hai and Sleeping Guard

Tamar Getter (born 1953) inserts quotations from European master paintings into works that relate subversively to her Israeli context. In 1920, the northern Galilean outpost of Tel Hai was the scene of a military confrontation that resulted in the death of Zionist leader and officer Joseph Trumpeldor, in what went down in Israeli history as an inspiring act of heroism. No iconic visual image recorded the event or captured its symbolic significance, but in a 1954 guidebook Getter found a sketch of the yard where the events took place and made it the focal point of her early, important series “Tel Hai Yard”, 1974–78.

In Tel Hai and the Sleeping Guard, the face of a sleeping watchman taken from Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection, 1463, hovers above the sketch of the yard, an ironic replacement for the sacred tomb that was being guarded in the Christian masterpiece. Instead of the face of of Jesus, we have a secondary figure who was derelict in his duty and therefore missed the miraculous event of the resurrection. The skeptical attitude towards Zionist and Christian foundational stories communicated by this sleeping guard leaves little room for hope or redemption

פיירו Piero della Francesca, Resurrection, 1463, Museo Civico di Sansepolcro, Italy

Tamar Getter, Tel Hai and Sleeping Guard (Version 1 Remade), 1978/2016

Green blackboard color and China Marker Dixon 92 on plastic sheet

Collection of the artist

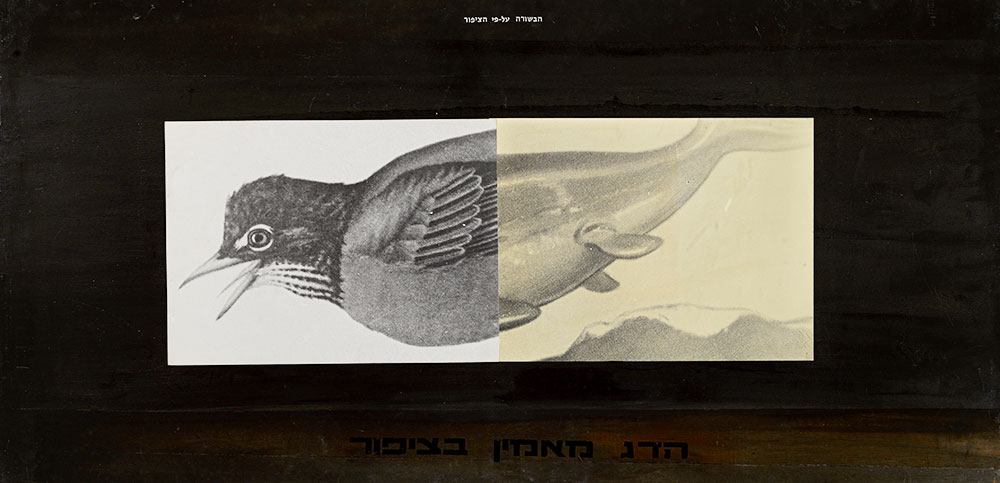

Michal Na'aman, The Gospel According to the Bird

Michal Na’aman (born 1951) engages with Christian themes and the figure of Jesus in three main ways: via textual references; through her use of symbols such as the cross and the fish; and in the surface of many of her paintings, which resembles lacerated, bloody skin.

The title of an early work, The Gospel According to the Bird, clearly alludes to the New Testament. It fuses a fish – Christianity’s most ancient symbol – with a bird, which symbolizes the Holy Spirit. In concept, Na’aman’s hybrid creature borrows from Greek mythology (the centaur, and so on) or European fairy tales (“The Little Mermaid”), but there is something disturbing about her unfamiliar pairing. The bird may be the bearer of the gospel, but now that it has been joined to a flightless fish, it cannot deliver its good tidings. Thus disruptions of sound and image are interconnected in a reflexive artwork that address questions of verbal and visual perception.

Michal Na’aman, The Gospel According to the Bird, 1977

Acrylic, photographs, and Letraset on plywood

Tel Aviv Museum of Art

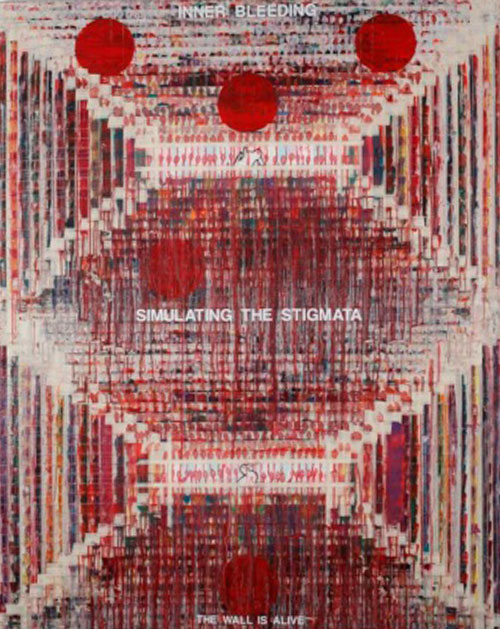

Simulating the Stigmata

In the early 1980s, Na’aman began working with layers of masking tape, applying paint over images visible deep within the canvas. Illusions of perception recurred in paintings containing what may either be a rabbit’s ears or a duck’s bill. Over time, these works became increasingly congested, the strips of masking tape resembling bandages through which the paint seeped and dripped like blood. The artist then added phrases with overtly Christian associations, some of them relating to Jesus’ dual nature, so that the works themselves expressed the idea of the physical incarnation of God’s word.

Michal Na’aman, Simulating the Stigmata, 2011

Oil and masking tape on canvas

Gordon Gallery, Tel Aviv

Signs of the Cross

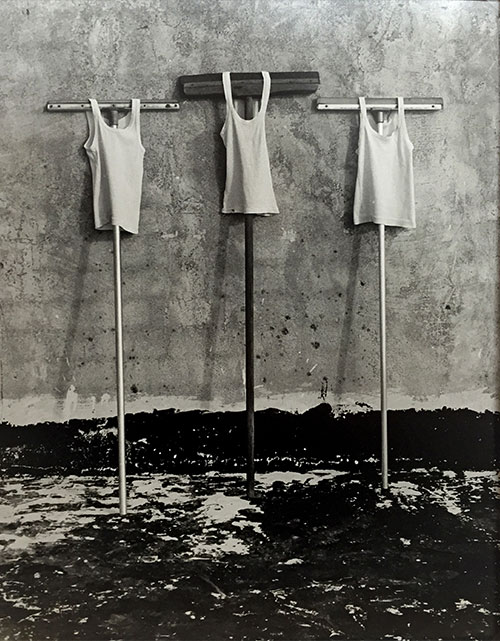

Efrat Natan, Roof Work: Golgotha

“The message we carried in our hearts was not attired in fancy raiment” (Labor Zionist leader Berl Katznelson, 1946)

Jesus is invoked indirectly, but with intensity and originality, in the work of Efrat Natan (born 1947). Natan, whose kibbutz background plays an important role in her artistic concerns, relates the story of Jesus to the ethos shared by Israel’s founding generation. In Zionist visual culture, a frail, tormented body was associated with the weak Jew of the Diaspora, but Natan inverts the Zionist ideal of the muscular New Jew by likening the crucified Christ to the self-sacrifice of the pioneers.

In the course of her 1979 performance piece Roof Work, she positioned three squeegees (quintessentially Israeli floor-washing tools) upside-down and hung three simple undershirts (for her, the emblematic garment of the kibbutznik) on them “to dry.” The composition recalls countless Christian artistic depictions of Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified with a thief on either side. Through this minimalist action, Natan connected religious faith and secular daily life, high culture and material sparseness, spiritual redemption and arduous physical labor.

Efrat Natan, Roof Work: Golgotha, 1979

Gelatin silver print

Photograph of installation: Yehudit Itach

Joshua Borkovsky, Vera Icon

“. . . who is the image of the invisible God” (Epistle to the Colossians 1:15)

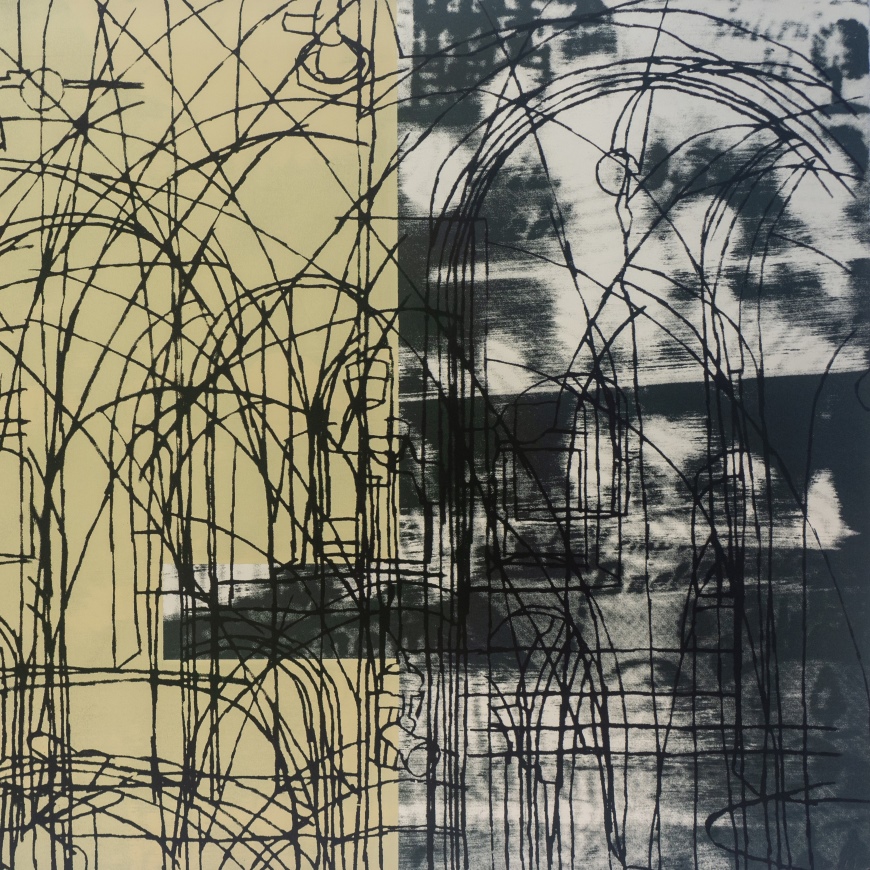

In the work of Joshua Borkovsky (born 1952), Jesus only appears by way of his preeminent visual symbol: the cross. Borkovsky’s art investigates the elusiveness of the image, and his monumental cycle (thus far numbering more than 30 paintings), Vera Icon, raises questions about whether there can be such a thing as a “true image.” Such is the meaning of the words 'vera icon', which are related to the Christian legend about Veronica, a compassionate woman who wanted to wipe the sweat off Jesus’ face as he passed by her on his way to Golgotha. According to the story, the beads of sweat imprinted his facial features on her kerchief, creating a picture that demonstrated the dual nature of Christ: a man of flesh and blood whose divinity could be seen in the miraculous way in which his image was preserved. Borkovsky’s Vera Icon cycle reproduces, not the face of Jesus, but the cross – countless vertical and horizontal lines in shades of green. Each new work reveals variations, so that together these paintings testify to the artist’s tireless quest to arrive at the one true image.

Five canvases in the cycle are devoted to the subject of the Annunciation: the angel Gabriel’s revelation to the Virgin Mary that, through the Holy Spirit, she would conceive a child who “shall be called the Son of God” (Luke 1:26–35). As testimony to the miracle of God’s incarnation in the human form of Jesus, this scene has profound importance for Christian dogma. In the 15th century, it was broken down into five spiritual and emotional stages, according to which Mary was troubled by Gabriel’s words (conturbatio) and pondered them (cogitatio), questioned the angel (interrogatio), and then humbly submitted (humiliatio) and accepted her destiny (meritatio). Borkovsky’s treatment of the five stages of the Annunciation through the image of the cross suggests that the end of Jesus’ life was present already at the moment of his conception.

Joshua Borkovsky

Annunciation

Contrubatio

Cogitatio

Interrogatio

Humiliatio

Meritatio

From the “Vera Icon” cycle, 2011–16

Distemper on gesso on wood

Collection of the artist, Jerusalem

I, We, and the Other: From the late 1980s until Today

Since the late 1980s, Jesus has featured in Israeli art as a symbol of sacrifice – representing victims of war, of society, and of the establishment – and also as an artistic alter ego. This Jesus is not divine: he is a human being with an identity (Jewish, Israeli, Palestinian), a universal suffering figure, or a representation of the artist’s pain. He has not been invoked to serve a national agenda by condemning Christian anti-Semitism or by signaling the rebirth of the Jewish people; he is an accessible Jesus to be identified with on an individual level. And finally, of course, the figure of Christ is central to Western culture and thus to the artistic arena that Israeli creativity has become part of.

Photography and video art dominate this section of the exhibition. Some works liken actual images from a harsh reality to the torment and crucifixion of Jesus, while others are staged works inspired by the story of the Passion.

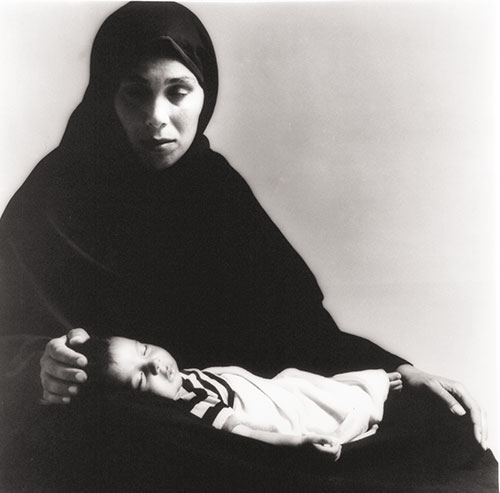

Micha Kirshner, Aisha el-Kord, Khan Yunis Refugee Camp

Around the beginning of the First Intifada (uprising), Micha Kirshner (1947 - 2017) photographed Aisha el-Kord, a Palestinian mother who had been imprisoned in Israel. She holds her sleeping daughter, wrapped in a striped cloth reminiscent of a tallit, a Jewish prayer shawl, in a pose that seems very familiar. This could be a Madonna and Child, but it also resembles the Pietà. In Christian art, the symbolism of the sleeping infant Jesus in his mother’s arms – at times wrapped in a shroud – alludes to his future death. In Kirshner’s photograph, the sleeping baby in the tallit- ike cloth does not invoke Jesus as a persecuted Jew (as in Chagall’s work), but takes the role-reversal in a different direction and uses Christian iconography to portray Palestinian victims of the Israeli occupation.

Micha Kirshner, Aisha el-Kord, Khan Yunis Refugee Camp, 1988

Gelatin silver print

Boaz Tal, Self-Portrait with My Family, Pietà with Notre-Dame

The photography of Boaz Tal (1952–2012) relates to artistic masterpieces on mythological, biblical, and Christian themes. His pictures are domestic scenes, however – they take place in his own house, and he, his wife, and his children play the characters he photographs. In this version of a Pietà, set amidst the everyday clutter of an Israeli home, the artist himself is being held by his wife. Their two older children stand over the pair, while their little daughter photographs them. Tal’s eyes look back at her, but also at the television screen behind him, which shows an image of Notre-Dame (Our Lady, that is, Mary) Cathedral in Paris. There is more than a little irony in this photographer’s melding of a traditionally tragic and dignified presentation of the dead Jesus, icons of Christian high culture, family dynamics, and the banality of the middle-class living room.

Boaz Tal, Self-Portrait with My Family, Pietà with Notre-Dame, 1992

Lambda print

Estate of the artist

Erez Israeli, Untitled

With himself and his personal life at their core, the video works of Erez Israeli (born 1974) relate to the country’s army ethos and attitudes towards the (male) body. The two videos seen here are at one and the same time private, universal, and profoundly embedded in Israeli culture.

In God, Filled with Compassion, the artist’s mother clasps her seemingly lifeless son to her breast while standing upright, as in Michelangelo’s unfinished Rondanini Pietà. The soundtrack is the memorial prayer sung at every Israeli soldier’s funeral: El Male Rahamim (God, filled with mercy). These words also begin the poem by Yehuda Amichai that speaks so bitingly of God’s compassion: “God-Full-of-Mercy . . .If God was not full of mercy, / Mercy would have been in the world, / Not just in Him.” The juxtaposition of this charged prayer with an image recalling the death of Jesus intensifies Erez Israeli’s cry of protest at the cruel military reality of the country.

In his untitled video from 2006, Israeli lies on his mother’s lap in the classic pose of the Pietà. The background song, written by Idan Raichal and sung by the legendary Shoshana Damari, is entitled “A Leaf Carried by the Wind.” Although its words have nothing to do with soldiers or death, its singer cannot be dissociated in Israeli collective memory from her renditions of wartime classics. The mother’s act of feather-plucking, absurd as it may be, calls to mind the death of another son: the mythological Icarus, who made himself wings but was killed when he flew too close to the sun.

Erez Israeli, Israeli' Untitled, 2006

Video, 4:10 minutes

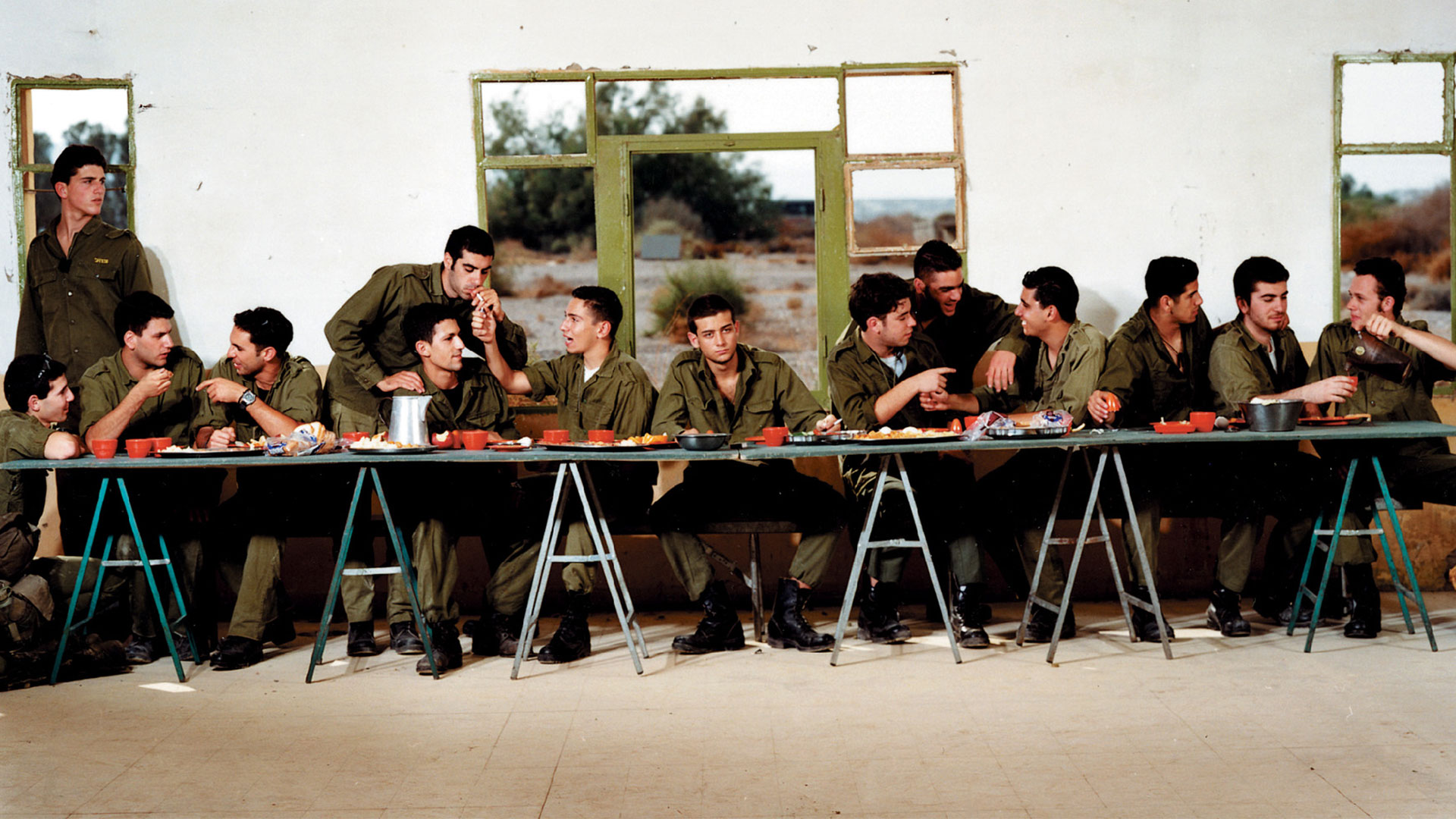

Adi Nes, The Last Supper

“Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me.” (Matthew 26:21)

What appears to be a routine photograph of soldiers eating is, in fact, a meticulously staged scene. It was inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, depicting one of the most dramatic oments in the story of Jesus: his pronouncement that one of his disciples would betray him, leading to the Crucifixion, the ultimate sacrifice for the sake of humanity. Unlike Leonardo, Nes (born 1966) does not portray a scene filled with tension and emotionally fraught gestures. As his relaxed soldiers talk and joke, only the central figure occupying the seat of Jesus seems preoccupied as he looks away from his comrades and out into the distance.

Facing the risk of dying in battle, the youthful soldiers are at the most dangerous moment in their lives. Nes’s analogy between the iconic Christian scene and Israeli reality conveys a political message about commitment and sacrifice. Like Christ’s apostles, the soldiers act on behalf of a power stronger than themselves. But they are also victims of a geopolitical constellation over which they have no control and may be betrayed. The bullet holes in the wall, cigarette smoke, and bitten apple are symbols of transience, reminding us that this might indeed be their last supper.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, Covent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

Adi Nes, Untitled, 1999

Chromogenic print

Sigalit Landau, Standing on a Watermelon in the Dead Sea

Sigalit Landau (born 1969) stands on a watermelon in the Dead Sea. Since it is difficult to keep anything submerged in the very salty water of the sea, in order to perform this tricky balancing act, she stretched her arms out to her sides in a pose of crucifixion. Christian representations of the doctrine of Mary’s Immaculate Conception show her standing on a globe, the white moon. In a work that suggests both life and death, the conception of the mother and the death and rebirth of her son, symbolized in the crucifixion, cannot be separated.

Sigalit Landau, Standing on a Watermelon in the Dead Sea, 2005

Video, 5:21 minute loop

Collection of the artist

- May 01

- May 01

- Apr 26May 02May 03May 09May 10May 16May 17May 23May 24May 30May 31

- May 03May 10May 17May 24May 31

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Apr 21Apr 28May 05May 12May 19May 26

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Apr 22May 06

- May 06May 27

- May 06

- May 06

- May 06Jun 10

- May 08May 15May 22May 29

- May 08May 15May 22May 29

- May 08May 15May 15May 22May 29

- May 08

- Apr 24May 08May 15May 22May 29