Jerusalem Rebuilt

Boris Schatz's Utopia Revisited

Special exhibit

-

November 28 2018 - March 1 2019

Curator: Amitai Mendelsohn

-

"From above the city appeared wonderfully beautiful, spread out over hills and valleys, with its many high towers, domes, flat roofs, gardens, pools, and bridges suspended above the valleys."

Boris Schatz, Jerusalem Rebuilt, 1918

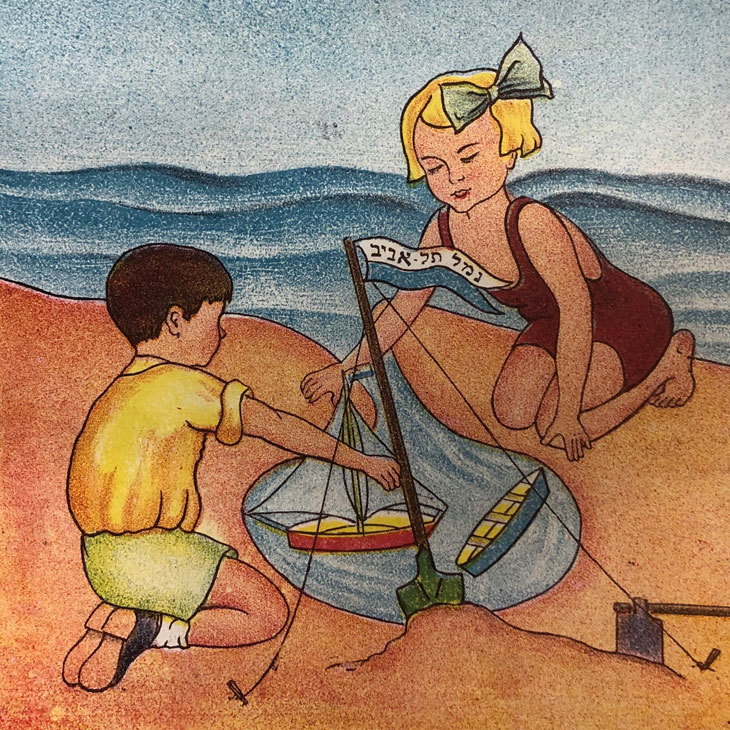

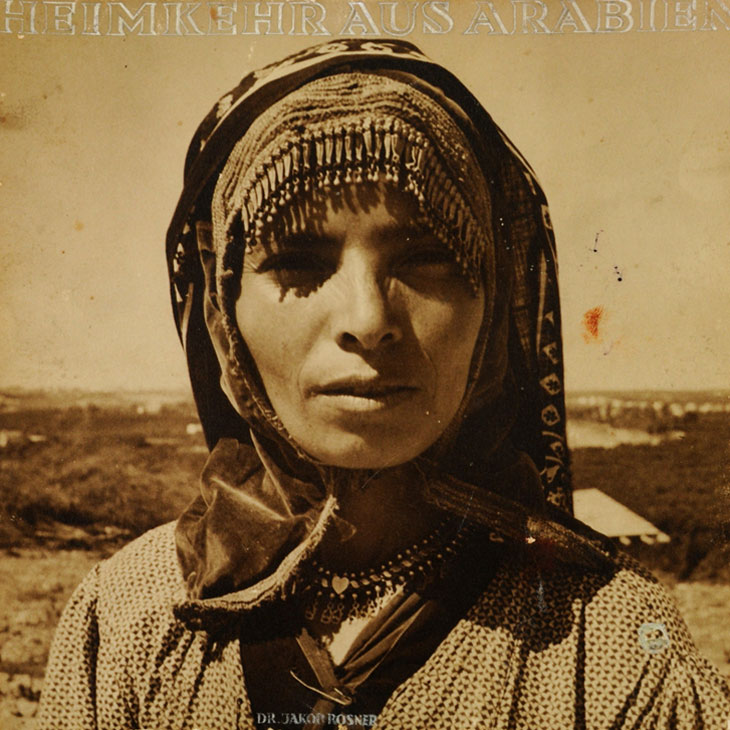

In December 1917, towards the end of the First World War and only days before the British captured Jerusalem and established their mandate over Palestine, Boris Schatz – founder and director of the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts and considered the father of Israeli art – was exiled by the Ottoman authorities from Jerusalem to the Galilee. In the following months, when the Bezalel School was temporarily shut and its future seemed bleak, Schatz wrote his utopian novella Jerusalem Rebuilt: A Daydream. There, he described the land of Israel – and Jerusalem in particular – as he envisioned it in a hundred years' time. In the spirit of the utopian novels of the period, of which the best known is perhaps Theodor Herzl's Altneuland (1902), he exposed his political, economic, and social approach, and – above all – his vision regarding the arts.

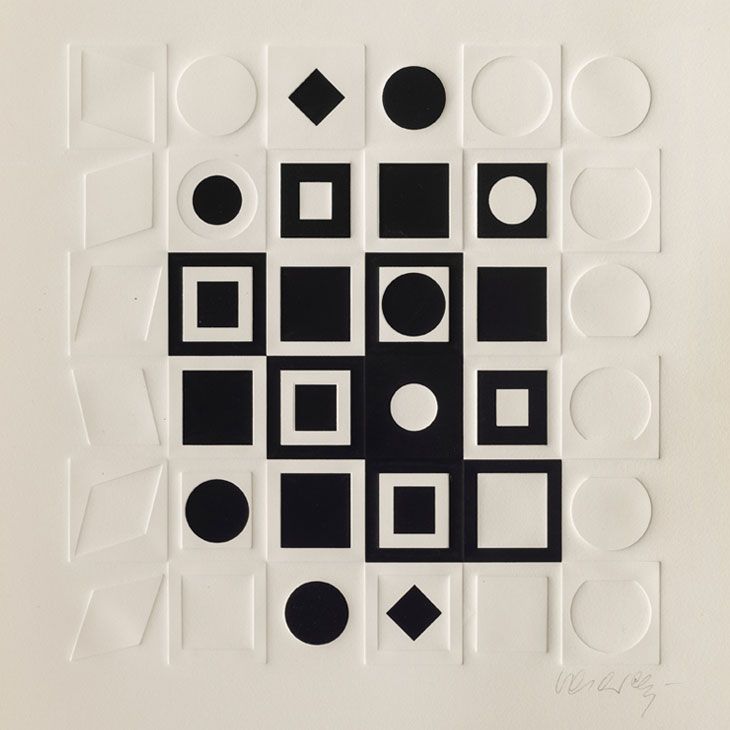

In his drawing for the cover of Jerusalem Rebuilt, the artist Ze'ev Raban chose to depict the story's opening scene, in which Schatz fantasized he saw on the roof of the Bezalel School the biblical artist Bezalel ben Uri, who built the Tabernacle and its implements, and for whom Schatz named the School. In the imagined scene, Bezalel tries to lift up Schatz's spirits by inviting him to travel to the future and visit Palestine in 2018. Jerusalem – and the entire country – is ruled in a socialist and egalitarian spirit by cooperatives made up of farmers, factory workers, and artists, all of whom work in a safe and ecologically friendly environment, enjoying technological advances that benefit the world without polluting it. Manual labor has been restored to its former glory and the fine arts have regained their natural place as human-made rather than industrial crafts. The Bezalel School has grown dramatically, now employing many people in its workshops. Local life and culture is manifestly Jewish, though carried out in a modern rather than halakhic spirit. The Third Temple has been built on the Temple Mount, after the Muslims have agreed to transfer the Dome of the Rock to the vicinity of Jaffa Gate. Rather than serving as a place of cult and sacrificial offerings, it is now a museum that constitutes the cultural and spiritual core of Jerusalem and of the country as a whole, resonating with Schatz's vision of art as the loftiest of all human endeavor.

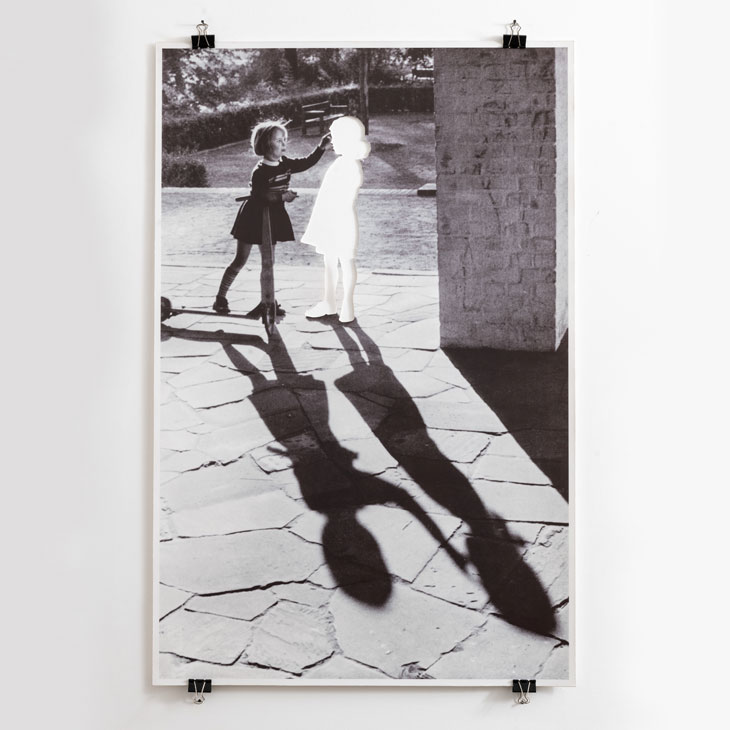

Displaying Boris Schatz's book in today's Jerusalem, one hundred years after he wrote it, offers the opportunity to reflect on the very notion of utopia (which literally means "no place" – somewhere that is nowhere). Schatz could not have predicted the complex reality of 2018 Israel and the depth and obduracy of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He envisioned a bright future characterized by tolerance and mutual respect, in which people would live in full harmony with themselves and their surroundings and art would be a fundamental part of their existence. While contemporary reality may not quite have achieved this goal, the Museum aspires to realize something of Schatz's vision of the modern Temple as a center of creative activity, inspiration, and spiritual life in the heart of Jerusalem.

- May 14

- Apr 18May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 16Apr 18Apr 30May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 19Apr 20Apr 27May 03May 04May 07May 10May 11May 17May 18May 21May 24May 25May 28May 31

- May 06May 20May 27

- May 20May 27

- May 21May 21May 21May 28May 28May 28

- May 21May 28

- May 21

- May 21

- Mar 12May 21