Hadassa Goldvicht

The House of Life

On display in Venice

-

May 9 2017 - November 26 2017

Curator: Amitai Mendelsohn

-

,

- Artist: Hadassa Goldvicht

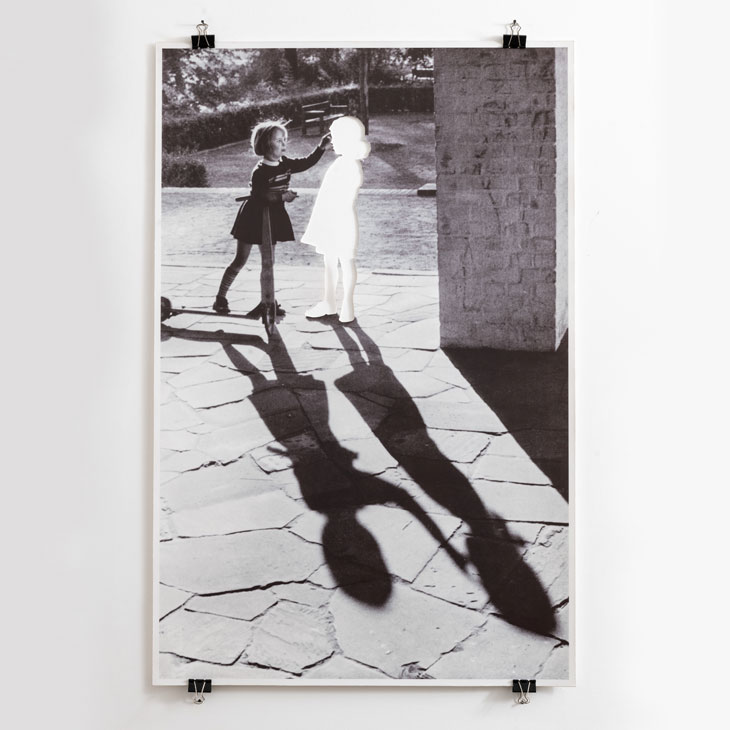

In 2013, Beit Venezia, the Venice Center for International Jewish Studies, invited Israeli artist Hadassa Goldvicht to create a video piece about the Jewish community there. She began interviewing members of the community, who spoke about the changes Venice has undergone in the past decades and the profound effects that globalization and the ever-increasing quantities of tourists have had on them. But what began as a documentary-like work took a dramatic turn when Goldvicht met Aldo Izzo, guardian of the Jewish cemetery in Venice and director of its burial ceremonies. Once a captain on a ship, in the past thirty-five years he has taken upon himself the thankless task of caring for the cemetery, tending the stones and the vegetation and working for its restoration. Izzo became the center of Goldvicht’s video installation.

There are two Jewish graveyards on the Lido island: the ancient cemetery, which was active from 1386 to 1774, and the new one, still in use today. During the turbulent years in which the ancient cemetery was active, tombstones – and at times even the graves’ contents – were often desecrated, damaged, and removed. Aldo Izzo took it upon himself to restore the ancient graveyard and the violated honor of the Jews buried there. In a sense, this is his life’s work. Since the deceased are not necessarily buried beneath the tombs that display their names, the graveyard is in a sense fictional – a place designed by Izzo and the vicissitudes of time. As a child he recalls playing in the cemetery and hiding from the Fascists there. It is his space, his lifelong playground, where the living protect the dead and the dead protect the living.

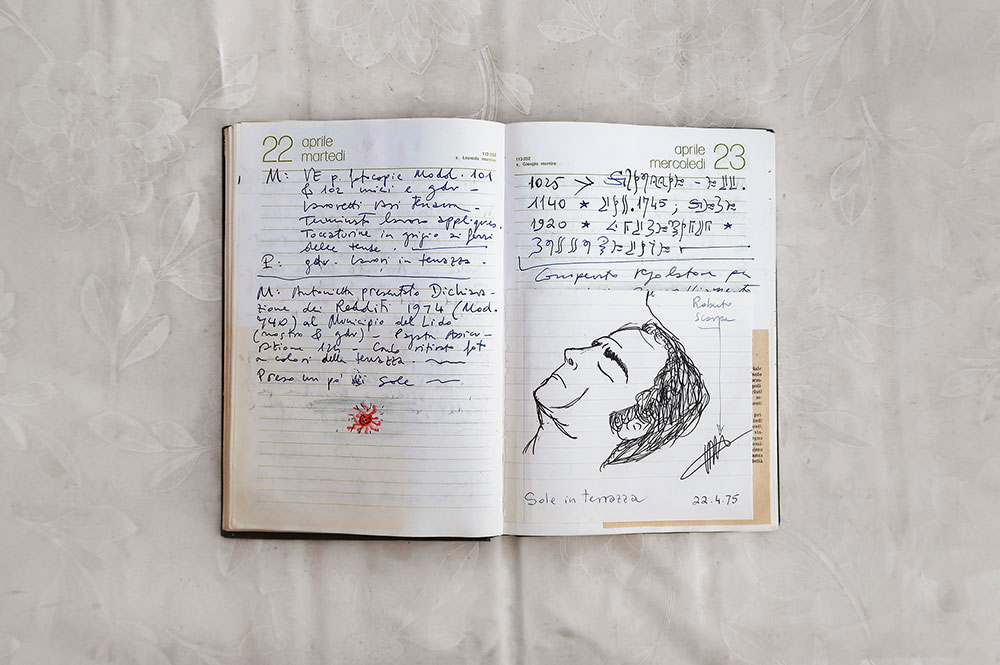

Hadassa Goldvicht’s works raise questions about the complex relationship between life and art. Like Izzo who carefully places tombstones and mummifies his beloved turtles, Goldvicht starts from the concrete but aims for the poetic and the transcendental. The exhibition leads us from close-ups of the ancient graveyard, through interviews with Aldo Izzo in his home and in the cemetery, to images from his diary – a kind of captain’s log that he kept throughout the years and that is both personal and historical. In a large projection, we see Izzo’s library juxtaposed with the broken stones of the graveyard. In another video Izzo shows an interesting phenomenon: some of the headstones have a hole in their bottom part. These holes, he explains, is where the soul will appear when the dead arise. It is through the multilayered figure of Aldo Izzo that the essence of Goldvicht’s artistic journey is revealed. His role as keeper of the cemetery can be compared to that of the artist. Through Izzo’s lifelong work in preserving the memory of the dead and through Goldvicht’s artistic intervention in it, the cemetery becomes a house of life. Thus, Izzo can be seenas a personification of the artistic process itself – the quest for an afterlife.

The exhibition is presented in collaboration with Meislin Projects, New-York.

- Apr 24Apr 25Apr 26

- Apr 19Apr 20Apr 27May 03May 04May 07May 10May 11May 17May 18May 21May 24May 25May 28May 31

- Apr 01Apr 08Apr 15Apr 29

- Apr 02Apr 02Apr 02Apr 09Apr 09Apr 09Apr 16Apr 16Apr 16Apr 30Apr 30Apr 30

- Apr 02Apr 09Apr 16Apr 30

- Apr 16Apr 18Apr 30May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- May 06May 20May 27

- May 07Jun 25