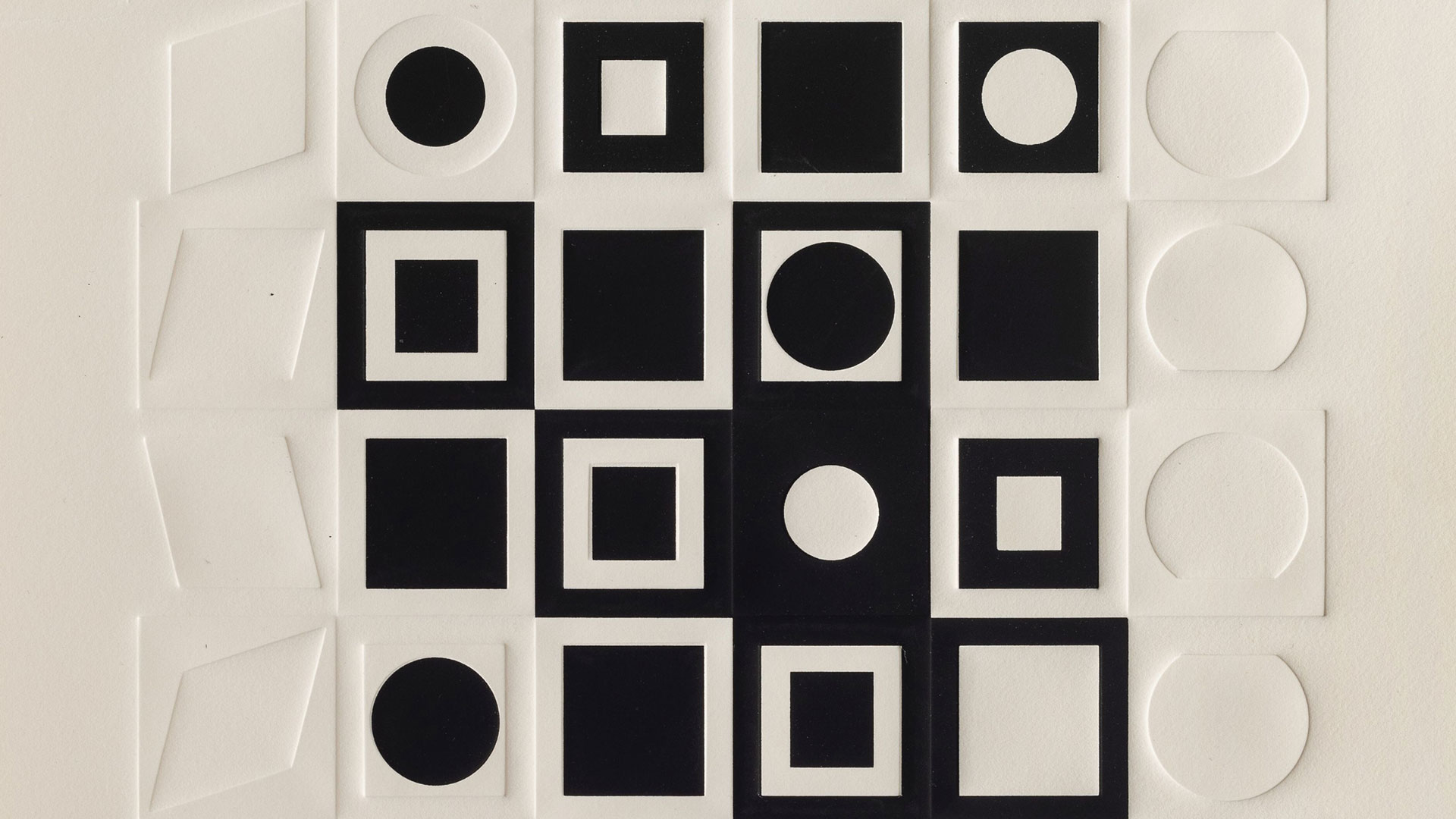

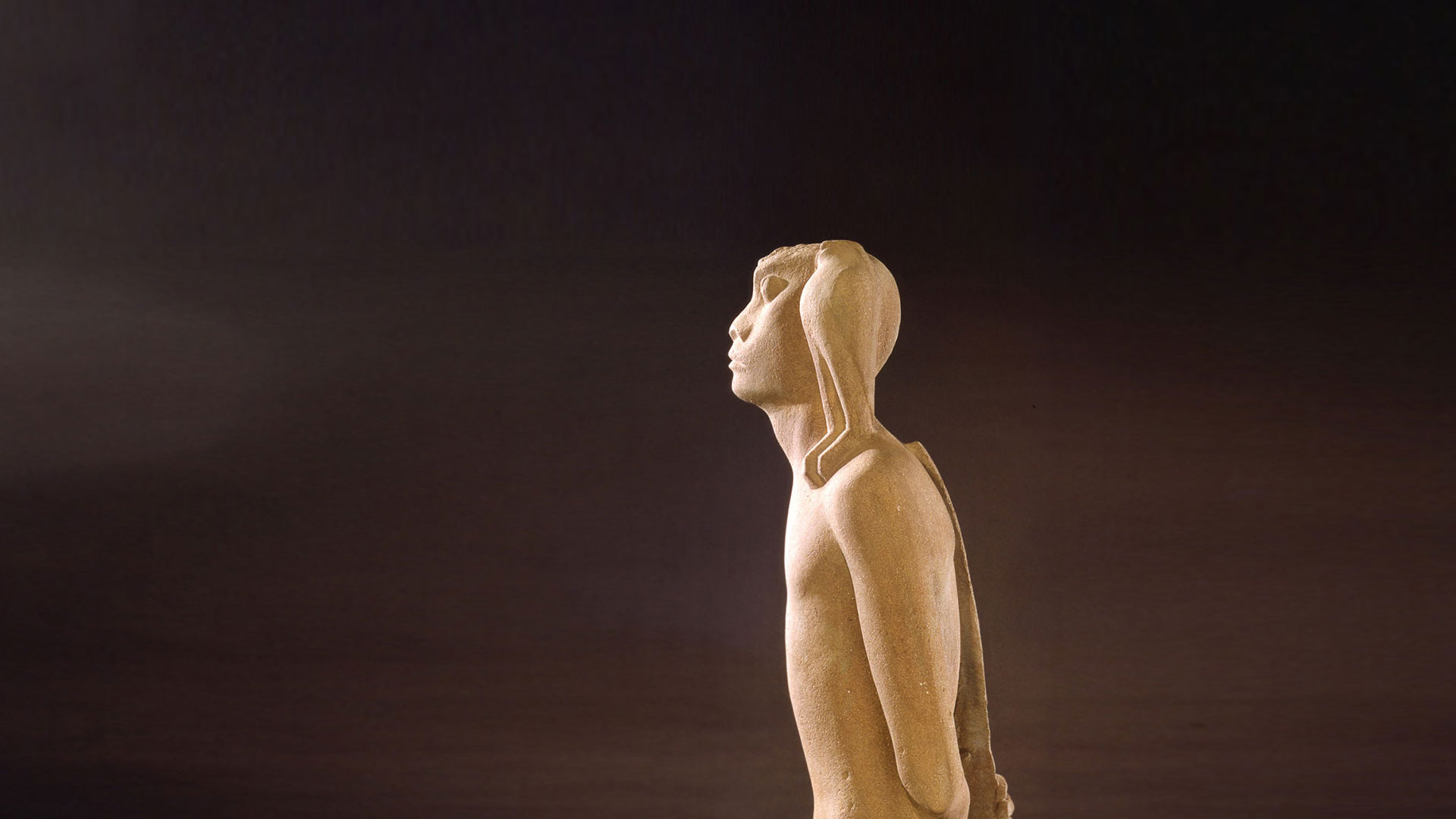

Joan Miró’s Spanish Dancer

Variations on a Theme

-

February 27 2013 - June 29 2013

Curator: Adina Kamien-Kazhdan

-

- : Joan Miró

Mini-Symposium (Lectures in English); In conjunction with the closing of the exhibition Thurs June 20|Entry to the event at 6:30 pm; Event begins at 7 pm|No extra charge|Sponsored by the Joan Lessing Modern Art Symposium Fund

Flamenco's sensuous display of the upper torso, articulate hand gestures, and percussive footwork inspired Joan Miró (1893–1983) to produce more than 30 sketches, drawings, paintings, and collages of Spanish dancers between 1921 and 1981. These witty, playful, and at times aggressive works are rendered in a variety of styles – from realism and cubism to surrealism, from figurative painting to abstract collage and construction. Miró's figures transform the popular image of the erotic dancer, with her cascading dress, dangling earrings, hair combs, and traditional mantilla veil, introducing a modernist language of forms that grapple with the artist's complex national identity. Two works in the Israel Museum collection – Miró's 1924 drawing Spanish Dancer and his Painting (Spanish Dancer) of 1927 – stand at the core of this exhibition. They are surrounded by an ensemble of works that illuminate the artist's recurrent imagery, establishing a highly refined vocabulary of visual signs that become fused with the Spanish Dancer.

Born in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia (a politically autonomous region in North-East Spain), and dividing his time between Paris, Barcelona, and his family farm in the Catalonian village of Montroig, Miró was drawn throughout his life to the themes of Spanish dance, bullfighters, and Catalan peasants and villages – themes that reflected a deep engagement with his cultural heritage. From 1923 to 1930, Primo de Rivera's dictatorship suppressed the Catalan language and outlawed institutions of Catalan nationalism, attempting to impose a unified model of culture on all of Spain. Miró and other artists and critics in his circle were caught between two opposing forces: a recalcitrant Catalan culture that they rejected and a passionate commitment to Catalan nationalism. Miró's choice to pursue the theme of the Spanish Dancer evinces a desire to reinvent a "Catalan voice" and use what was perceived as an icon of "Spanishness" in France to express his origins in a personal yet universal avant-garde language. Miró encountered individuals and frequented cafés, night clubs, and flamenco locales that were central to Barcelona's cultural life in the early 20th century. Among his contemporaries were internationally renowned dancers such as La Argentina, La Argentinita, and Carmen Amaya, and Miró enjoyed a lifelong relationship with choreographer and dance theoretician Vicente Escudero. Musical works by composers such as Enrique Granados and Manuel de Falla, who were inspired by Andalusian flamenco, contributed to Miró's interest in the motif. Like these artists, Miró sought a personal language that would combine native Spanish traditions with avant-garde modernism. His images can be interpreted in light of poet and dramatist Federico García Lorca's notion of artistic inspiration, "duende." Like flamenco, this state of trance or heightened emotion – which has been described as "a holistic combination of groundedness and the mystical"* – requires a vivid awareness of death, a connection with the soil, and an awareness of the limitations of reason.

Thanks to all those who assisted us with our research: Teresa Montaner, Curator of the Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona; Pilar Ortega, Curator of the Successió Miró, Palma de Mallorca; Particia Molins, Curator at the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; dance historian Ninotchka Bennahum, New York. Special thanks to art historian Robert S. Lubar, New York University, and to Shem Shemi,* Jerusalem, creator of the film Por el Flamenco.

- Apr 19Apr 20Apr 27May 03May 04May 07May 10May 11May 17May 18May 21May 24May 25May 28May 31

- Apr 24Apr 25Apr 26

- Apr 01Apr 08Apr 15Apr 29

- Apr 02Apr 02Apr 02Apr 09Apr 09Apr 09Apr 16Apr 16Apr 16Apr 30Apr 30Apr 30

- Apr 02Apr 09Apr 16Apr 30

- Apr 16Apr 18Apr 30May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30