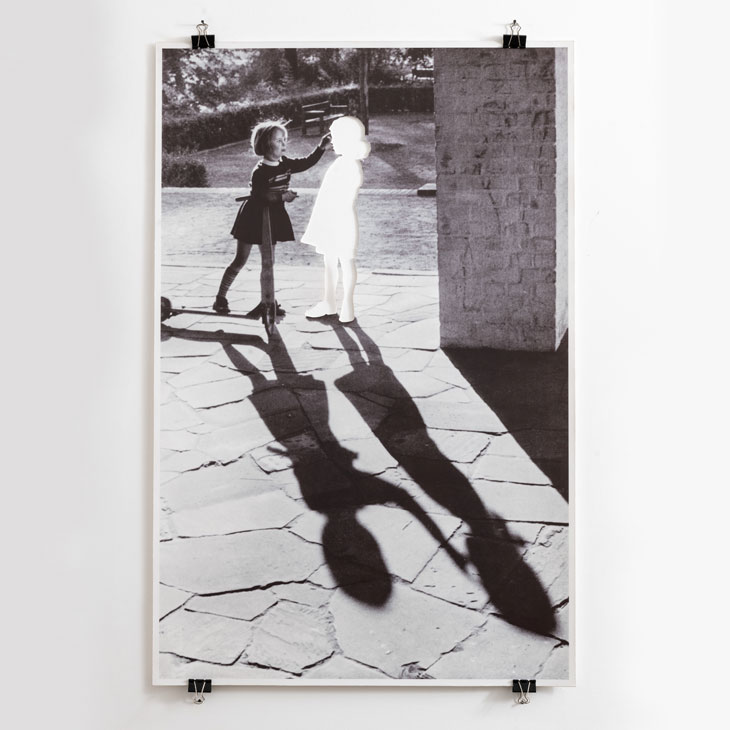

No Place Like Home

-

February 25 2017 - August 19 2017

Curator: Adina Kamien-Kazhdan

-

-

Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Martha Rosler, Louise Bourgeois, Mona Hatoum and others

Introduction

An ironing board becomes absurd and threatening, the doors of a house are displaced, a glass of beer sprouts a tail.

By altering material, scale, perspective, or by employing hybridization, fragmentation, and relocation, artists transform domestic objects in order to change our relationship with them and to provoke a fresh response to the familiar.

No Place Like Home, an experimental exhibition, deals with the readymade and its artistic offspring, the creative act, and the relationship between art and its context. What happens if we restore a transformed object to its "natural” place within a quasi-home in the Museum? Visitors at the exhibition play the part of family – we become Alice in Wonderland under a gigantic table leg.

Domestic spaces, objects, and materials have increasingly emerged as subject and source of inspiration in modern and contemporary practices. In the transition from functional object to artwork, the domestic object becomes a tool in the investigation of gender roles, housework, collecting, and hoarding, and a means of reflecting on the home as the central site in the formation of family and memory, national and cultural identity.

No Place Like Home brings objects-turned-artworks into a mock home within the Museum to trigger new perspectives on the objects and on our own lives. The exhibition’s theme, range, and layout, and its IKEA-inspired catalogue, offer the visitor an experience of a "home" that is at once familiar and disorienting. Inspired by architectural plans, the exhibition is organized as a series of “rooms.” Installing works within a domestic space challenges the legacy of the modernist white cube, and semi-transparent partitions aim to reveal the permeability of influences and emotion.

More than half of the exhibition’s 120 works are drawn from the Museum’s own collections, supplemented by central loans from sister institutions, private collections, galleries, and artists. Our exhibition celebrates the centennial of Marcel Duchamp’s iconic Fountain, and the 101st anniversary of the revolutionary Dada movement. In each room, artists of the past 100 years are brought into a dialogue, engaging and interacting with one other. This curatorial choice underscores the spiritual legacy of concepts developed from Dada to today, from the readymade to a contemporary exploration of displacement and the global artist's own itinerancy.

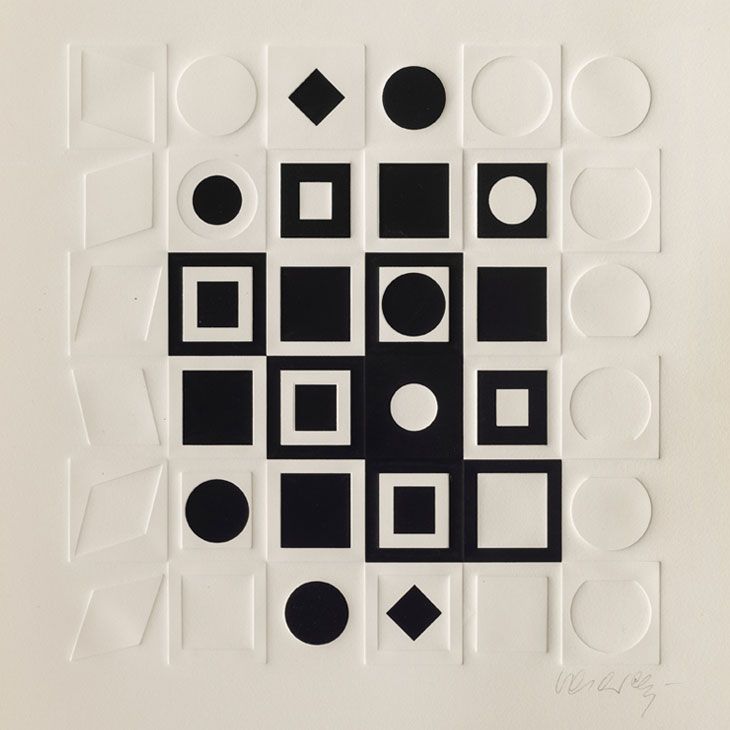

Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade

The readymade or “transformed readymade” is a leitmotif of No Place Like Home. In a 1963 interview, Marcel Duchamp radically de-deified the artist with this self-effacing proposal: “A readymade is a work of art without an artist to make it.”

An innovative creative entity blurring traditional boundaries and categories of art history, Duchamp's readymades intentionally elude simple definition. Readymades are commonplace objects displayed within an art context. They are pre-manufactured commodities of mass production, often unaltered except for the addition of the artist’s signature and inscription. In this case, the creative act consists of choice or selection, rather than manual execution.

In 1913, Duchamp chose mass-produced objects that would not attract him by their beauty or by their ugliness. He later installed the “readymades” in his studio in an unusual way, suspending some from the ceiling and nailing one to the floor. In this way, he not only gave the object a "new thought," but also escaped "from conformity," which dictated that art be hung on the wall or presented on easels. While the readymades served as objects of private contemplation, they also became the artist’s most important means for questioning categories.

The readymade undermined notions of creativity and authorship, and rejected the “retinal” and manual aspects of art in favor of a conceptual approach. Characterized by what Duchamp called a “lack of uniqueness,” the readymade challenged the status, value, and aura of the original work of art.

Duchamp's complex ideas have been adopted and modified at varying levels of understanding; his iconoclasm, originality, and conceptual approach, and his imaginative use of materials and media have influenced art up to the present.

Andreas Slominski, Vogelfall (Bird Trap)

Marcel Duchamp, Door: 11, rue Larrey, Paris

Doris Salcedo, La Casa Viuda VI (The Widowed House VI)

House/Home

Homes are dwellings of the mind. The English language has two distinctly different words that refer to the place of dwelling: home and house. The term house identifies a physical structure that enables domestic activities, but a home is also a mental state characterized by a sense of belonging, protection, love, and shelter. A home is a place located between the physical reality and a conceptual idea, between past memories and future aspirations. Home straddles the threshold separating private intimacy and the public world of buildings and culture.

A house evolves into a home through accumulative processes. Layers of meaning and emotion develop between space and the person inhabiting that space. From caves and primitive huts to contemporary skyscrapers, we rely on architecture to shelter us from the unpredictability of nature. Because it is rooted deeply in our hearts, home is the place in which misunderstanding and misrecognition are most painful. No other architectural structure houses such a range of human actions and emotions.

The Uncanny

In his seminal 1919 essay “The Uncanny,” Sigmund Freud clarified that the word “uncanny” in German – unheimiliche – is rooted in a word that means “unhomelike” or "unhomey," which describes an uncomfortable state in which something familiar (homey = heimlich) becomes estranged. The uncanny is scary and disturbing, because it is simultaneously homey and unhomey, a familiar experience made disconcertingly unfamiliar.

Using intimate and maternal terms, Freud described the uncanny as “the place where everyone dwelt once upon a time and in the beginning...whenever a man dreams of a place or a country and says to himself, still in the dream, ‘this place is familiar to me, I have been there before,’ we may interpret the place as being his mother’s genitals or her body.”

The dialogue between the homey and unhomey, familiar and strange, excited artists in the interwar avant-garde. They used domestic imagery and themes as a means of exploring family dynamics and the nurturing of sexual codes of behavior from childhood, but also as a mode of profane illumination – encouraging the return of repressed memories, fears, and desires. A restaged banal object could act as a trigger, making “something which ought to have remained hidden…come to light.”

Works by Dadaists, Surrealists, and later artists inspired by them, focused on this sexualized understanding of the home, and often emphasize the mutability of gender. The Freudian alignment of the home and the maternal with desire and fear, nourishment and fetishism, is reclaimed and celebrated as a primordial, affective power.

Kitchen

Lebanese-born, Palestinian-British artist Mona Hatoum focuses on themes of violence, oppression, and exile, suggesting an unsafe world. Domestic objects are transformed into sinister look-alikes in a series of sculptures based on items of furniture. Grater Divide, kitchen grater enlarged to humorous dimensions, becomes a partition or wall between political opponents, or perhaps a warning against the oppression of bourgeois life and fixed gender roles.

Hatoum has said, “I see kitchen utensils as exotic objects, and I often don’t know what their proper use is. I respond to them as beautiful objects. Being raised in a culture where women have to be taught the art of cooking as part of the process of being primed for marriage, I had an antagonistic attitude to all of that.” Building on Sigmund Freud's 1919 essay on the uncanny, Hatoum said, "Home and the uncanny, or the familiar turning unfamiliar, is the basis of so many of my works. Whether playing with scale by enlarging harmless kitchen utensils until they become threatening or passing electricity through everyday objects and investing them with a kind of animism, or using incongruous materials that make the objects or furniture unusable or dangerous, this is all about the uncanny.”

American artist Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen portrays the paradigmatic middle-class, suburban America seeking vengeance before the spectator. The artist stands at a kitchen table, wearing an apron, facing a camera, and naming each kitchen utensil in the room in turn in a deadpan tone. She brings the piece to a close by slicing out the letters U, V, W, X, Y, and Z in the air, with her arms and two kitchen knives. It is a feminist call to arms, an insistence on bringing politics home. For Rosler, woman needed to resist her “pacification” by patriarchal society: to speak out and name her oppressor.

Birgit Jurgenssen, Stove-Apron and Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen

Utility Room/Pantry

Yayoi Kusama is a versatile artist whose painting, sculpture, installation, and performance work are all influenced by her obsessive nature. In this work, an ironing board becomes absurd and threatening. The steam iron, placed face down on the board, seems about to scorch and flatten the sea of erect phalluses covering the surface. Kusama uses white paint and domestic craft skills (sewing and stuffing fabric) to refashion a readymade steam iron and ironing board into a landscape of mushroom-like phalli. She transforms the quintessentially male object and symbol of power into a feminine, intimate, benign one. She expresses her fear of male domination and attempts to symbolically possess and defy patriarchal authority. Kusama’s work – crafted between the atomic bombing of Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and the Vietnam War (1955-75) – countered a culture of machismo, war, and dehumanization at a time of great civil unrest and brutality in American foreign politics.

Yayoi Kusama, Untitled (Ironing Board)

Pop artist Andy Warhol's works explore the relationship among art, celebrity culture, and advertisement that flourished in prosperous USA of the 1960s. His Brillo Boxes are precise, custom-made copies of the commercial packaging of this product. While they obey the imperative that art imitate life, they also raise questions about the definition of art, authorship, authenticity, and value.

Warhol's Brillo Soap Pad reflects the emerging American consumer culture of the 1960s and the growing power of brand recognition. Furthermore, it challenges the notion of originality through the use of appropriation and seriality. If Warhol transformed a mundane commercial product into a work of art, how did that transformation happen? Considering Warhol made numerous Brillo Boxes and sold them to art collectors and museums, his works can also be considered mass-produced consumer goods.

Bathroom

Marcel Duchamp’s enduring impact is evident particularly in the exhibition’s “Bathroom,” displaying Fountain, which epitomizes the 100-year-old conceptual revolution of the readymade through the artist’s act of appropriating and designating a porcelain urinal as a work of art. It still elicits discomfort in the viewer.

In 1917 Duchamp, under the alias Mr. R. Mutt, sent in an inverted urinal – entitled Fountain – for exhibition at the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The Society rejected Fountain, and it disappeared from the display. An unsigned editorial published in the May 1917 second issue of the magazine, The Blind Man (edited by Duchamp himself, Henri-Pierre Roché, and Beatrice Wood), defended Fountain in an article entitled, “The Richard Mutt Case.” The anonymous author protested the piece’s rejection and justified its display. He rejected accusations cast upon Fountain's immorality and vulgarity, and denied criticisms of plagiarism, underscoring the centrality of choice, the artist’s thought process, and the insignificance of the manual act:

“Whether Mr. Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.”

Duchamp’s growing influence peaked in the 1960s, within movements spanning Pop art, Nouveau Réalisme, Fluxus, Conceptualism, Minimalism, and Performance art, which incorporated, appropriated, or developed the use of the readymade, and drew on Duchamp’s rethinking of art, the role of the artist, and art institutions.

The position of Duchamp’s urinal is restored to its original functional location. Homages to Fountain by more contemporary artists are shown adjacent: Robert Gober’s Double Sink (1985), Rachel Lachowicz’s Untitled (Lipstick Urinals) (1992), and Janine Antoni’s Lick and Lather (1993). Encouraged by Duchamp’s own plays on identity and the androgynous, these artists address the following themes: public and private space, the social objectification of women, and concepts concerning replication, casting, process, and the body.

Rachel Lachowicz’s Lipstick Urinals, a series of three miniaturized, upright urinals cast in glossy lipstick red, reconfigure Duchamp’s iconic Fountain (1917) and alludes to his female alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy. Lachowicz’s use of lipstick draws our attention to the mouth as the orifice that breathes, eats, spits, speaks, and shouts, the place of both pleasure and abjection. Society demands women “perfect” the mouth by applying cosmetics.

Rachel Lachowicz, Untitled (Lipstick Urinals)

Janine Antoni uses materials one would find on a shopping list – lipstick, chocolate, lard, soap – to critique conventional notions of femininity, as well as the masculinity of much Modernist art. She cast her self-portrait in chocolate and in soap, completing the forms by licking the chocolate bust and washing the soap one. Antoni subverts masculine methods of sculptural casting, while also undercutting portraiture as a symbol of the “fixed” identity, drawing the spectator close to smell or touch the works. Using her own hands and tongue – an emphatically physical, unskilled means of production – to fashion their different stages of figuration or erasure, makes a subtle but potent sociopolitical comment on woman’s place and unseen work in the home. As with Lacowicz’s lipstick urinals, in Antoni’s work, the senses celebrate feminine expression and creativity – in contrast to the dominant, phallic brush. She enjoys the formal contrast of light and dark materials and its invocation of racial difference. The Freudian alignment of the home and the maternal with desire and fear, especially.

Janine Antoni, Lick and Lather, 1993

Winnicott and the Transitional Object

The teddy bear comes to represent the mother in her absence, symbolizing security, attachment, and love. These feelings are almost unrelated to the actual physicality of a specific stuffed animal, and could have been attached to an old T-shirt or a blanket, sometimes referred to by nicknames.

Psychoanalyst Donald Woods Winnicott coined the term "transitional object" for objects that provide psychological comfort at bedtime, and especially in unusual transitional situations. They straddle reality and unreality and occupy a "transitional space" that is an intermediate developmental phase between the psychic and external reality. Winnicott claimed that one should never ask whether the transitional object is real or unreal.

The word “home,” like the word "mother,” evokes layers of meaning that go beyond physical and biological dimensions. Think of the word “mother”: she is the womb and the breasts, nature and nurture, protection and punishment. She is yearned for and overwhelming. Mother is what Winnicott called the total supportive environment, the condition that allows a baby to survive. The word “home” has a similarly wide semantic field, because of its central role as the place of intimacy, safety, and dwelling – a place that enables survival.

Japanese artist Takashi Murakami He works in fine arts media – such as painting and sculpture – as well as what is conventionally considered commercial media – fashion, merchandise, and animation. He is known for blurring the boundaries between high and low arts. Mr. DOB is Murakami's first signature creation. It references famous pop-culture icons such as Mickey Mouse, Sonic the Hedgehog, and Doraemon. Merging language and cartoon imagery, Murakami's Mr. DOB shows how an icon emerges as an object of mass consumption and circulates as a distinctive registered trademark to be used, reused, bought, and sold. The cute, presumably male, mouse/monkey hybrid character is both humorous and menacing. His name is a contraction of the Japanese slang expression "dobojite" (which means “why?”) from silly gags found in early 1970s manga. Murakami’s Mr. DOB is an example of the Japanese popular cultural phenomenon of “kawaii” (cuteness), along with Manga comics and animation, and the fictional character Hello Kitty. Similarly, Mr. DOB embodies the contrast between “kawaii” and its homonym “kowai,” (scary) – cuteness as a counter-reaction to the Japanese culture of violence represented by the Samurai and the influence of American culture post-atomic Bomb. Here Mr. DOB is born as an oversized helium balloon.

Anila Rubiku, Casa all’italiana - Superleggera

Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset, Boy Scout

Gaston Bachelard and The Poetics of Space

Many artists shown in this exhibition turn to the house as a means of exploring the concept of home as an intimate place where reality and dream, the corporeal and the political, are inextricably linked.

In his seminal book The Poetics of Space (La Poétique de l'EspaceFrench philosopher and phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard examined the experience of space, focusing on the home. He wrote:

If I were to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace. Thought and experience are not the only things that sanction human values. The values that belong to daydreaming mark humanity in its depths....

Now my aim is clear: I must show that the house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts and memories and dreams of mankind. The binding principle in this integration is the daydream.

Louise Bourgeois draws the spectator into eroticized environments that relate to repressed childhood memories. In Arched Figure (1993), home is not the bed beneath the arched figure's body but the (missing) maternal body, whose absence emphasizes the physical and psychological trauma of the exposed form. Until the late nineteenth century, hysteria was deemed a female malady, caused by a "wandering womb" (the word hysteria is Greek for womb). Neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot took a more scientific and analytical approach to the disease and understood hysteria as a mental illness. Freud furthered this research, viewing hysteria as an emotional, internal affliction caused by previous trauma that could affect both males and females. Lying on a wooden bed, its mattress covered in sackcloth, Bourgeois's thin, bronze male body with its jutting ribs arches backwards and clenches its toes. The figure's headlessness imbues the figure with universality.

Louise Bourgeois, Arched Figure

Barbara Bloom, The Reign of Narcissism

Curator: Adina Kamien-Kazhdan

Assistant curators: Neta Peretz, Adi Shalmon

Exhibition design: Studio de Lange/ Chanan de Lange, Yulia Lipkin

Photography: Elie Posner, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The exhibition was made possible by:

Grace Frankel and Hanns Salzer Levi, Marbella, Spain

IKEA Israel and Matthew Bronfman, New York

The donors to the Museum's 2017 Exhibition Fund:

Claudia Davidoff, Cambridge,Massachusetts, in memory of Ruth and Leon Davidoff

Hanno D. Mott, New York

The Nash Family Foundation, New York

- Apr 24Apr 25Apr 26

- Apr 19Apr 20Apr 27May 03May 04May 07May 10May 11May 17May 18May 21May 24May 25May 28May 31

- Apr 01Apr 08Apr 15Apr 29

- Apr 02Apr 02Apr 02Apr 09Apr 09Apr 09Apr 16Apr 16Apr 16Apr 30Apr 30Apr 30

- Apr 02Apr 09Apr 16Apr 30

- Apr 16Apr 18Apr 30May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- May 06May 20May 27