European Imprint

Jacob Pins and German Expressionism

-

April 8 2017 - September 19 2017

Curator: Ronit Sorek

-

Prints

Introduction

This exhibition presents a selection from the Museum's collection of German Expressionist works on paper. Most of them were brought to Palestine in the 1930s by artists, art lovers, and collectors from central Europe and Germany in particular, who fled Nazism and hoped to create a small cultural haven in their new homeland. They gathered in Jerusalem, where they breathed new life into the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts and its accompanying museum, imbuing both with a fresh spirit that was very different from what either had known previously. Why did these émigrés donate their treasures? Most certainly out of generosity and a recognition of the importance of a public collection, but perhaps also out of a desire to distance themselves a little from the burden of this culture that had disillusioned them – and, during the period of austerity in the 1950s, also for financial reasons. The collection is therefore neither a meticulous record of the period and its artistic movements nor a comprehensive representation of the artists of the time: it is an assemblage of judicious personal choices that, in time, lay the foundation for the collection of the Museum's Prints and Drawings Department.

The tale of this exhibition therefore enfolds another story – one of forced emigration and reconstruction. The artist, collector, scholar, and teacher Jacob Pins represented this ethos in his own life, and the exhibition, marking the centenary of his birth, focuses both on his works and on those of German Expressionists – particularly members of the Brücke group – who influenced him.

Die Brücke

(The Bridge) was founded in Dresden in 1905 on the initiative of the artists Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, and Fritz Bleyl – all of whom shared a background in architecture but abandoned it to pursue an artistic career. Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein joined them in 1906, and Otto Müller in 1910. The members of this group, who worked together until 1913, sought to link German Great Masters such as Dürer and Cranach to modern art. They also wanted to bring works of art to the layman and build a bridge between the public and the anti-bourgeois forces of revolution. The visual inspiration for the name of the group may have been the bridges over the River Elbe in Dresden – the Blue Wonder Bridge, completed in 1893, which was considered a major technological achievement, and the historic August Bridge, on which reconstruction work began in 1902. Woodcuts played an essential role in the work of members of Die Brücke, as this simple technique afforded them a powerful means to convey the emotional and social content they wished to share with others.

Jacob Pins

Jacob Pins was born in Germany in 1917, and he immigrated to the land of Israel in 1936 as a member of the Shibboleth pioneer group. Five years later he settled in Jerusalem, where he remained until his death in 2005. In the early 1940s he studied at The Studio under Jakob Steinhardt, a significant figure in Expressionist art in Berlin. Unlike Steinhardt, Pins did not yearn for the landscapes of the Diaspora shtetl, nor did he seek to find them in the alleys of Jerusalem. On the contrary, he avoided Jewish symbolism, preferring natural scenes or themes with a moral. He was among the founders of the Jerusalem Artists’ House and taught graphic art at Bezalel for over two decades, until the late 1970s. Traces of German Expressionism can be seen in his work, together with an East Asian influence that permeated it from the late 1940s, when he began to collect Japanese woodblock prints.

Pins was a devoted and generous friend of the Museum’s Prints and Drawings Department, to which he donated works by himself and by other artists as well as bequeathing the collection of East Asian art that he had assembled over the course of some sixty years. His artistic estate is preserved in a museum dedicated to his work in his hometown of Höxter in Germany.

From the Exhibition

Jacob Pins, Israeli, born Germany, 1917–2005. Conclusion: Apocalyptic City, from the “Apocalypse” series. Woodcut, 1946. Gift of the artist, Jerusalem

This dramatic woodcut concludes the "Apocalypse" series that Pins created after he learned of his parents’ death and the magnitude of the destruction in Europe became clear. The first four prints in the series depict the horses of the apocalypse – representing plague, war, and death – which are mentioned in the Revelation to St. John in the New Testament. In this portrayal of the destroyed apocalyptic city Pins abandoned the use of Christian symbolism and focused instead on the collapsing buildings and on creating a rickety composition. He provided no geographic or national features that might identify the landscape and its people. This chilling depiction of the end of an urban civilization, wherever it may be, relieved him of the necessity for specific confrontation with Nazi evil.

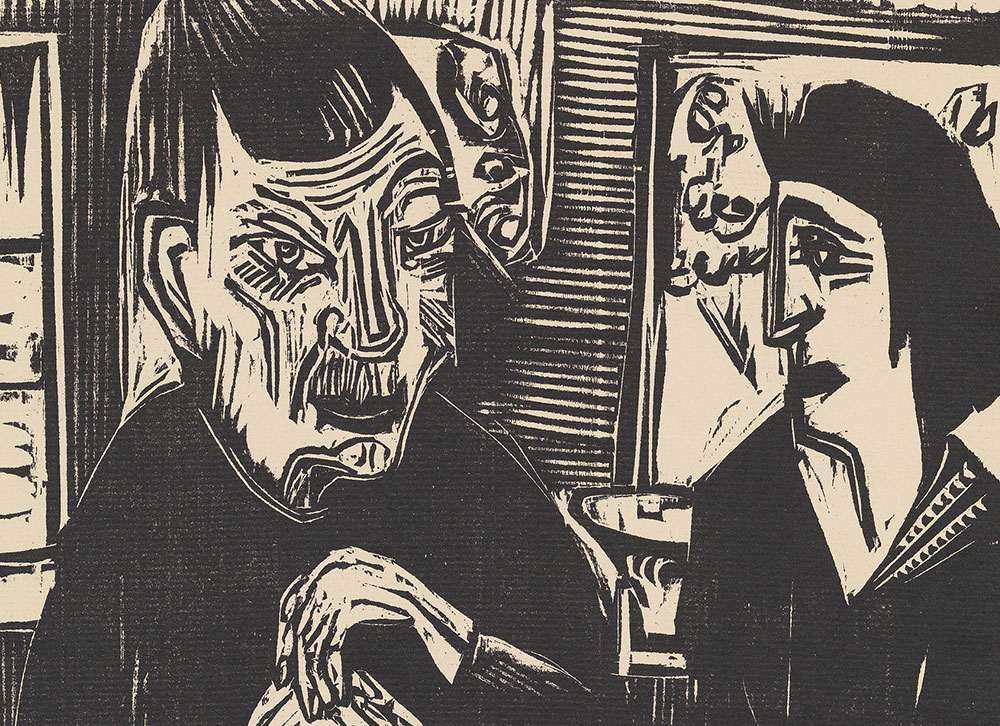

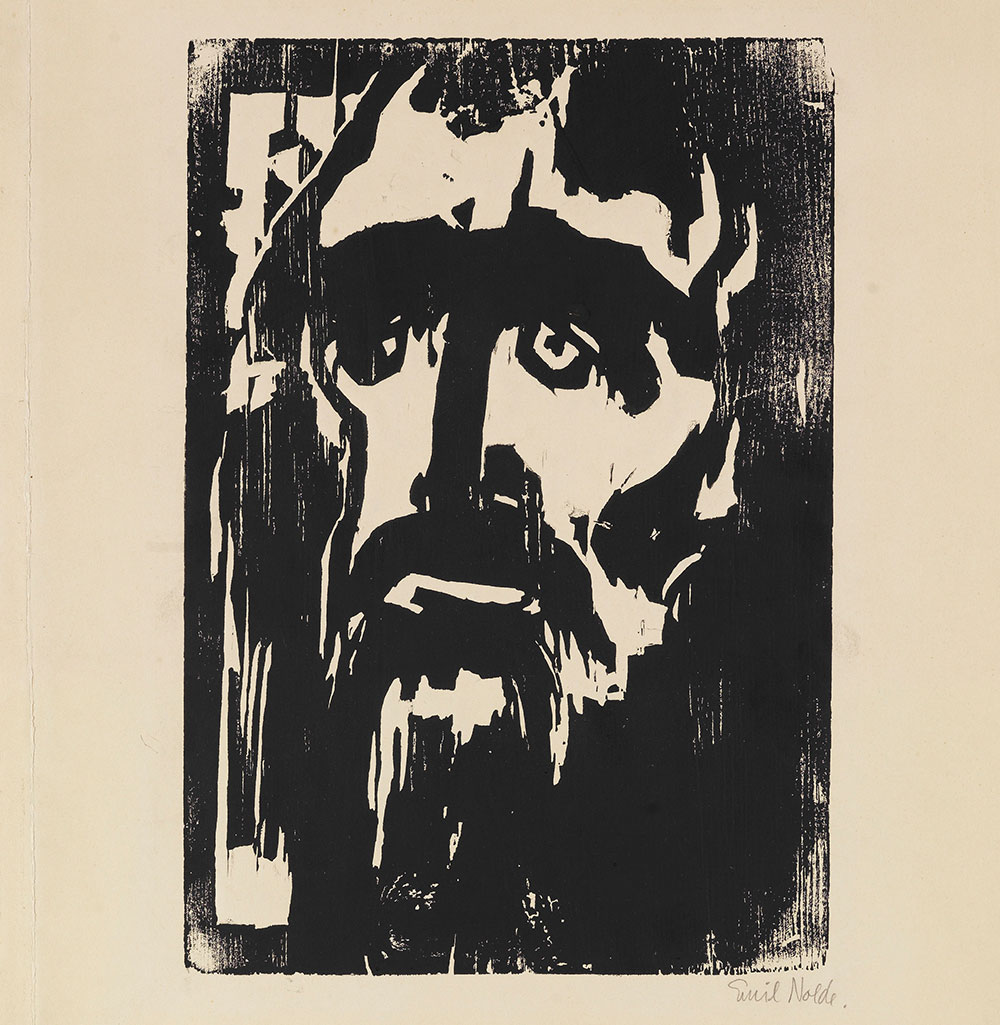

Emil Nolde, German, 1867–1956. Prophet. Woodcut, 1912. Gift of the Gidal family

Although Emil Nolde preferred to work alone, he accepted an invitation from the artists of Die Brücke and joined them for a year in 1906. Prophet belongs to a series of woodcuts on religious themes that he began after abandoning depictions of nature. Nolde seems to have identified with the role of the prophet, and, like a number of his Expressionist colleagues, attributed to himself a similar mission. He was the only one of them to support Nazi ideology, but his works were nonetheless declared to be “degenerate art.”

Käthe Kollwitz, German, 1867–1945. March of the Weavers, from the series “The Weavers’ Revolt”. Etching and aquatint, 1897. Gift of Ellie and Al Silver, Palo Alto, to American Friends of the Israel Museum

Just like Anna Ticho, Käthe Kollwitz took an increased interest in the lives of manual workers after she came into contact with them in the clinic run by her doctor husband. Unlike Ticho, however, who portrayed her figures with resigned compassion, Kollwitz had a clear objective in view: to protest against workers’ conditions. This etching was made after she had seen Gerhart Hauptmann’s play The Weavers, which portrayed the Silesian weavers’ rebellion of 1842 against the landowners. The revolt was a failure, but its repercussions influenced Kollwitz nonetheless and served as the inspiration for a series of prints depicting the suffering of oppressed workers.

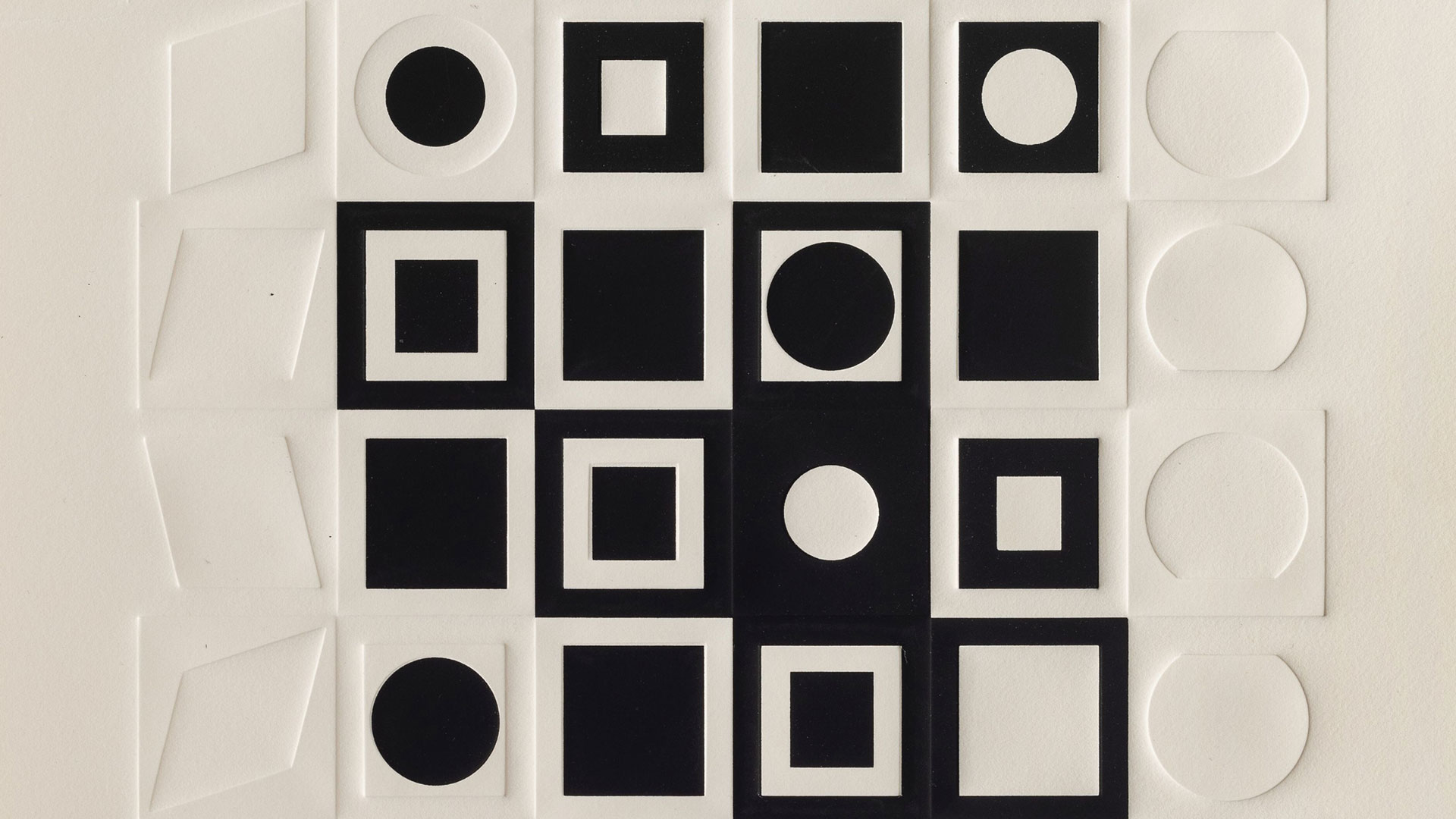

Jacob Pins, Israeli, born Germany, 1917–2005. Danse macabre (trial proof). Color woodcut, collage, and india ink (correction), 1957. Gift of the artist, Jerusalem

Danse Macabre is a mature version of an early print by Pins from 1945 on the same theme. Pins required four large preparatory studies before creating the later print, in which theatrical figures, including the clown he liked so much, appear together. Despite the presence of death in various roles and guises, this print possesses a sense of humor and power that is absent from the earlier version. Pins was familiar with the traditional representations of the danse macabre – an allegory dating back to the 15th century – in European art, and included in his work the two forms that personify death, as a dancing partner and a violinist. The work’s grotesque aspect is likewise borrowed from European tradition, which encouraged mortals to recognize the inevitability of death.

- Apr 19Apr 20Apr 27May 03May 04May 07May 10May 11May 17May 18May 21May 24May 25May 28May 31

- Apr 24Apr 25Apr 26

- Apr 01Apr 08Apr 15Apr 29

- Apr 02Apr 02Apr 02Apr 09Apr 09Apr 09Apr 16Apr 16Apr 16Apr 30Apr 30Apr 30

- Apr 02Apr 09Apr 16Apr 30

- Apr 16Apr 18Apr 30May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30