Christian Boltanski

Lifetime

-

June 1 2018 - November 3 2018

Curators: Laurence Sigal and Mira Lapidot

-

-

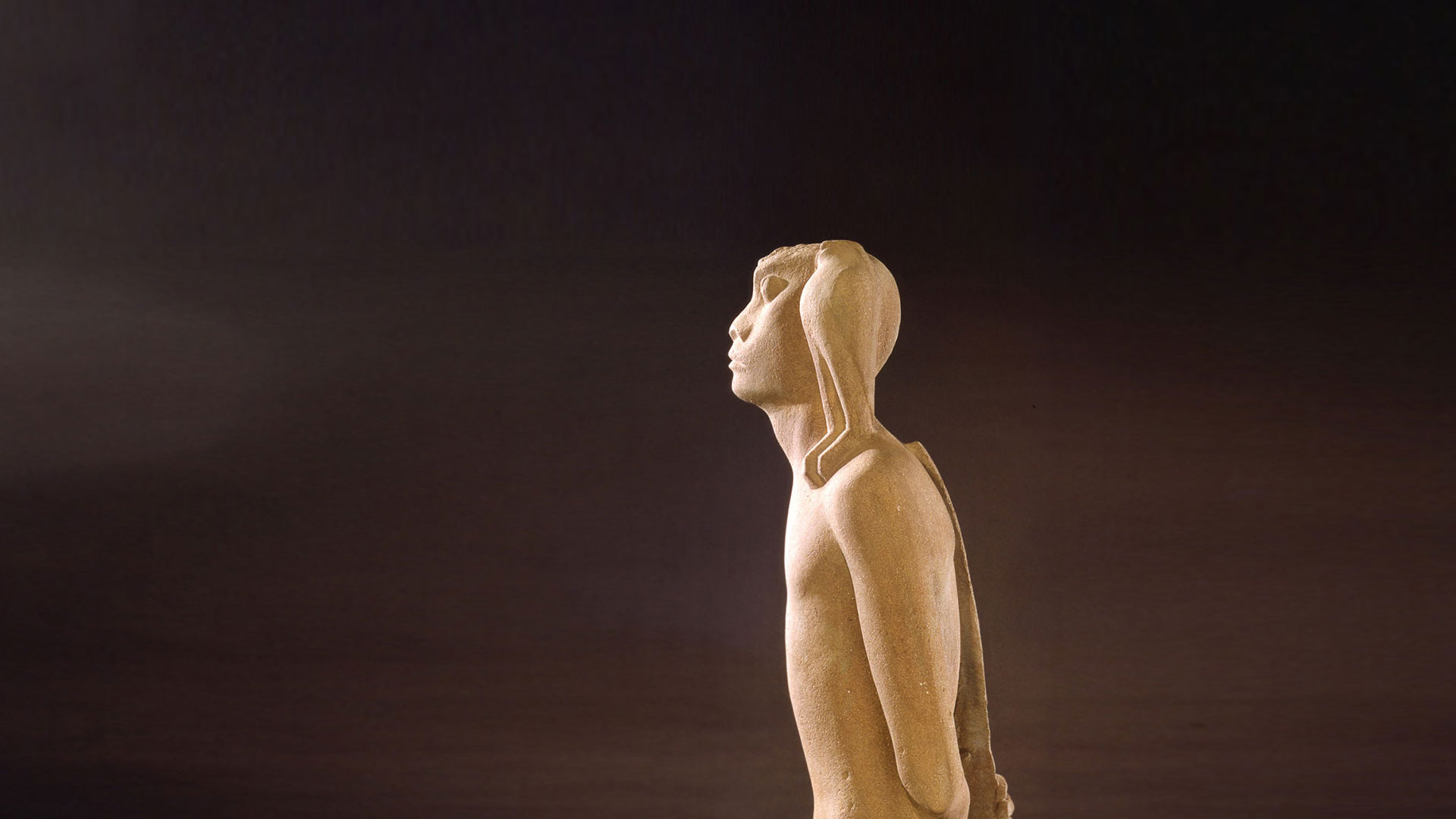

Christian Boltanski

“Central to my work is the fact that each one of us is unique and important and, at the same time, is destined to disappear. Most of us will be forgotten within two generations, after those who knew us have passed away.”

This simple and daunting realization lies at the heart of the lifework of Christian Boltanski, one of the great artists of our time.

Boltanski was born in Paris in September 1944, days after the city had been liberated by the Allies. His mother, a writer, came from a Catholic Corsican family. His physician father, born into a Jewish family from Odessa, hid under the floorboards for many months during the Nazi occupation. Boltanski’s art grapples in a profound, pioneering way with the long shadow World War II cast over the second half of the 20th century, but its significance extends far beyond that. Using modest materials and showing a singular sensitivity to the potency of images, he creates works which offer emotional immediacy while examining the complex and elusive nature of memory, both individual and collective. He never stops asking questions: What will remain of us after we have died? What is the meaning of time and its passing? How are we to preserve the memory of people who once lived and loved, feared and hoped?

Lifetime draws on an oeuvre spanning thirty years, but Boltanski regards the exhibition as one artwork, a complete story composed of successive chapters: his early altar memorials to unknown people; large-scale installations addressing the subject of fate; and recent video works filmed in primal landscapes and charged with the power of myth. The journey through the exhibition proposes an itinerary that begins in darkness but leads to light, solace, and perhaps even the possibility of a new beginning.

Altar to the Chases High School

Using modest materials – lamps, photographs, and old tin boxes – deployed with straightforward simplicity, Boltanski has raised an altar or memorial to those who are no longer. The artist rephotographed the individual images of four students in a 1931 class photo from a Jewish school in Vienna named after Rabbi Hirsch Perez Chajes, enlarging each one and clipping a lamp above it. Halos of light hover over the foreheads like bullet wounds. Many members of this high school class no doubt perished in the Holocaust, and the feeling of loss or sadness the images evoke cannot be separated from horror at the way their story ends.

In his lean visual vocabulary, Boltanski seeks to communicate with his audience, to give form to fundamental questions about life, death, and memory. The photographs are of specific people, but the process of enlarging and blurring their faces obscures identity. Instead of preserving individual likenesses, and thereby individual lives, even after death, the photographs signify absence and testify that we cannot hold on to the dead.

Altar to the Chases High School, 1987, Gelatin silver prints, tin boxes, lamps

Gift of Shawn and Peter Leibowitz, New York, to American Friends of the Israel Museum, in memory of Charles and Rosalind Leibowitz and Leila Sharenow

© Christian Boltanski, Photo © The Israel Museum by Meidad Suchowolski

Animitas (Dead Sea)

On a cliff overlooking the Dead Sea, three hundred Japanese bells have been arranged according to the configuration of the stars on the night Boltanski was born. When the wind blows, the bells on their fine metal reeds produce a delicate chime, while the clear plaques attached to each one shimmer in the light. Animitas was first created in 2014 in Chile’s Acatama Desert and has since been replayed in a number of settings, among them a snowy Canadian landscape and a forest in Japan. On the occasion of the present exhibition, the artist recreated the work in Israel, at a site known as Mitzpeh ha-Efes – “the Zero Lookout” – by the Dead Sea.

The result is something mythic that brings together traditions and beliefs of different kinds. Mitzpeh ha-Efes, marking sea level, separates the living kingdom of sky and mountains from an underworld, a kingdom of the dead – as the sea’s name indicates – at the lowest point on earth. In Japanese tradition, a slip of paper with a wish is attached to such bells, and each time the bell rings, the wish is carried on the wind to the powers that be. The work’s Spanish name means “small souls” and refers to the little shrines that are erected in memory of loved ones. Finally, the resonance between the French words for sea – mer – and mother – mère – seems particularly significant when we consider the womb-like shape of the Dead Sea and its primal setting.

Animitas (Dead Sea), 2017, HD color video, sound, © Christian Boltanski, Photo © The Israel Museum by Elie Posner

Eyes

Dozens of pairs of eyes – made-up, wrinkled, young, old – stare at us from translucent curtains. The gaze may be probing and direct, or it may be blank, and as we walk through these eyes we may engage with them or we may avert our own gaze. The images come from Greek passport photos, since Boltanski made the work while preparing an exhibition in Athens, but their origin is of no importance. In the most universal way, eyes and the gaze convey the essence of being human – the self. The gaze of the other forms our own sense of self as we walk through this labyrinth of looks.

Eyes, 2013, Printed fabrics, light bulbs, © Boltanski Christian

- Apr 24Apr 25Apr 26

- Apr 19Apr 20Apr 27May 03May 04May 07May 10May 11May 17May 18May 21May 24May 25May 28May 31

- Apr 01Apr 08Apr 15Apr 29

- Apr 02Apr 02Apr 02Apr 09Apr 09Apr 09Apr 16Apr 16Apr 16Apr 30Apr 30Apr 30

- Apr 02Apr 09Apr 16Apr 30

- Apr 16Apr 18Apr 30May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- Apr 18May 02May 09May 16May 23May 30

- May 02May 06May 09May 16May 20May 23May 27May 30

- May 06May 20May 27